Sámi Women in Reindeer Herding Families – Identity Tied to Recognition of Work Status

Sámi Women in Reindeer Herding Families – Identity Tied to Recognition of Work Status

By Ebba Olofsson

The author is teaching Anthropology and Methodology at Champlain Regional College in St-Lambert in Quebec. She also has an affiliation to the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Concordia University. She has done research with and about the First Nations and Inuit of Canada, as well as, the Sámi people in Sweden and Norway. Her research focuses on identity, gender, health, illness, and subsistence practices. She can be contacted at ebbaolofsson300@gmail.comor through ResearchGate and Linkedin.

Inga Mari Hætta cutting firewood with a chain saw while her daughter Inga Ellen Kristine Hætta looks on (Northern Norway in 1974). Photo: Hugh Beach.

As a Ph.D. student, I did research among the Sámi1 in Sweden, my focus was ethnic identity for persons with one Sámi parent and one Swedish parent (or other European ethnicity). Later in life, I have often taught about the Sámi in my Anthropology classes here in Canada. I used to show the documentary “Sami Herder” (1974) by the director Schuurman. In that film we get to know a Sámi reindeer herding family in Norway. We learn that the boy wants to be a reindeer herder when he grows up and the girl wants to marry a reindeer herder when she grows up. Watching that film many times, I started asking myself: how come the girl can’t become a reindeer herder herself - instead of her identity as a reindeer herding Sámi is linked to her future husband? I was also curious if that situation was a result of colonization of the Sámi or if it had always been like that.

The Sámi people

For those of you who don’t know the Sámi people, I would like to start with a short description of their way of living. The Sámi live in four different nations-states: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Kola Peninsula of Russia. The geographical area that is considered to be the core area of settlement of the Sámi is called Sápmi in Sámi language. The Sámi are traditionally pastoralists, herding and keeping reindeer. The reindeer are normally not kept in a corral (more than temporary at some occasions) or in a barn; instead they roam free in the forest or in the mountains. The Sámi reindeer herders move with the reindeer depending on season. In the winter session the reindeer are kept in the forest where they are sheltered from snow storms by trees; in the summer time the reindeer have the natural instinct to move to the coast or up in the mountains, away from the heat, mosquitoes and other parasites in the forest (Olofsson 1995).

Rönn’s map over Sápmi; northern Sweden, Norway, Finland and the Russian Kola Peninsula (Map Rönn 1961).

The Sámi are an Indigenous population which means that they lived in Sápmi long before the national states, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia, had extended their kingdoms to that area of the world. When the kingdoms of these national states moved in to the Sámi territory, they brought many changes to the Sámi way of living. The Sámi used to have their own religion, their own traditions, and the whole family used to travel with their reindeer according to the seasons. With the colonization of the Sámi and of Sámi lands, fewer and fewer people could continue with reindeer herding. Now in modern times, the reindeer herders are a minority in the Sámi collective, however, reindeer herding is still considered typical Sámi. Reindeer herding has become a symbol of Sámi identity (Olofsson 1995).

Changes in reindeer herding

Traditionally reindeer herding was organized in siida – families that worked together tending the reindeer. The siida consisted of siblings with their families – different constellations of brothers or/and sisters. Still today the siidais the socioeconomic unit for the reindeer herding. The Sámi traditional society (before colonization) was not an equal society – a person could own their own reindeer and there were families that were richer than other families. You also had young men working for richer reindeer owners. Men and women worked together and had different tasks in the reindeer herding (Pehrson 1964). Women in the traditional Sámi society had the right to own property and was normally in charge of the family economy. It was common for a widow to move back to her family and bring her property (Kuokkanen 2009). Thus, the women in the traditional reindeer society were not without decision power in the society. Men and women had different roles and power in different domains, complementing each other.

Inga Mari Hætta leading the reindeer, which are pulling sledges with supplies and equipment (northern Norway) in 1974. Photo: Hugh Beach.

The Swedish legislation of reindeer herding, implemented in 1886, changed the situation for the women in reindeer herding. The law stated that a Sámi woman marrying a non-Sámi would lose her right to reindeer herding and their children would not have the reindeer herding right either. A non-Sámi woman marrying a Sámi man would gain the reindeer herding rights and their children too. The legislation was changed in 1971 so that men and women came to have the same right to reindeer herding (Olofsson 1995). However, today we still see the effects of the old legislation of reindeer herding (Beach 1982) and also other factors such as the implementation of mandatory schooling of the reindeer herders’ children (Eikjok 2004).

Apmut Ivar Kuoljok is catching a reindeer with lasso in Sirges (Sirkas) sameby, in 1993.

Apmut Ivar Kuoljok is catching a reindeer with lasso in Sirges (Sirkas) sameby, in 1993.

Today, the men normally have the status as head of the household (husbonde)in the reindeer-herding unit of the extended family (siida). The husband (or brother, father) normally is the caretaker of the women’s reindeer, the reason being that he gains (and so also the family) more influence in the sameby(the economical and geographical unit of reindeer herding), since the member hasthe number of votes according to how many reindeer he or she has (Beach 1982). Women still own reindeer and work with reindeer herding. The implications of the status as non-reindeer herders in the samebyare many. Most women are not registered as members in the samebyand can’t vote in the sameby. The men receive the state subsidiaries for reindeer herding. It also becomes problematic for a woman to continue reindeer herding at divorce or if the husband dies. She risks losing the reindeer and the right for pasture for the reindeer (Kuokkanen 2009).

“Domestic” versus “public sphere”

Anthropological kinship and gender studies are assuming a distinction between “domestic sphere” and the “public sphere.” The “domestic sphere” is the household where the chores of the home are done, for example child rearing and cooking. The “public sphere” is outside the household where economical transactions and political decisions are being made. Typically, throughout history, we find the women in the “domestic sphere” and the men in the “public sphere” (Rosaldo 1974). Feminist anthropology has challenged this opposition (Collier and Yanagisako 1987) claiming that one needs to take the economic and political context of the “domestic sphere” into account. The distinction between “domestic” and “public” sphere, according to Barker (2005), is a separation that had its beginnings with the industrial revolution (factory work replacing household production). How does this separation play out in the Sámi reindeer herding?

Sonja and Apmut Ivar Kuoljok are having supper in their kitchen in their winter home in Jokkmokk (northern Sweden), in 1993. Photo: Ebba Olofsson.

The women in reindeer herder families often work outside reindeer herding in the “public sphere” as professionals (teachers, office clerks, at the store or at the pharmacy). Their income often makes it possible for the family to stay in reindeer herding and for the family members to keep their identity as Sámi. The women are also working in the “domestic sphere” by cooking, doing laundry, and driving the husband or brother to the reindeer pastures. Moreover, the women are also physically doing reindeer herding work in the “public sphere” by, for example, building fences and catching reindeer for marking or slaughter. Still they are not being recognized as full-time herders in the eyes of the law and often not in the eyes of the male reindeer herders. In a study done in 2013 of young female reindeer herders in Sweden, the participants describe themselves as being considered as having peripheral roles in the reindeer herding and not being at the center of reindeer herding as the male reindeer herders, not only in the eyes of the state but also by other Sámi persons (Kaiser, Näckter, Karlsson, Renberg, & Salander, 2015).

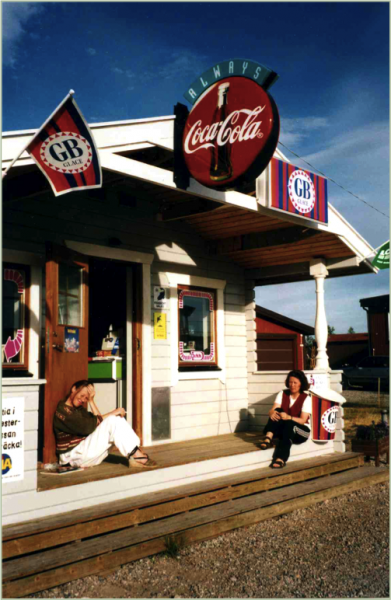

The sisters Lisbeth and Kerstin (from a reindeer herding family) are sitting on the porch of the family owned gas station in Övre Soppero (northern Sweden) in 1997. Photo: Ebba Olofsson.

Sámi identity is today associated with reindeer herding. Reindeer herding has become a male occupation. Thus, it is easier for men than women to identify themselves as Sámi. If girls wish to keep the Sámi identity they need to marry a reindeer herder. Still there are Sámi women who are full-time herders, but they are facing more difficulties than Sámi men. Sometimes it is too much to overcome these difficulties, mostly brought about by legislation, that they have to eventually give up the full-time reindeer herding (Olofsson, 2004).

Lisbeth is working with catching reindeer for marking at the summer land in northern Norway in 1997. Photo: Ebba Olofsson.

A distinction between “domestic” and “public sphere” is imposed on the reindeer herding families. Women work either in the “public sphere” outside reindeer herding or in the “domestic sphere” still outside reindeer herding. Reindeer herding has become a male occupation. Since Sámi identity is associated with reindeer herding, it becomes easier for men than women to identify themselves as Sámi. That’s why Ellen Inga Kristine, the girl in the film about the Sámi, needed to marry a reindeer herder.

This research has been published in a more extended version as book chapter titled “Inequality in Swedish Legislation of Sámi Reindeer Herding” in Global Currents in Gender and Feminisms: Canadian and International Perspectives published by Emerald Publishing. You can contact me on my email if you would like to read the full text and I can email it to you. You can also suggest to your university library to buy the book.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the editors of the Forage Blog; Kali Wade and Megan Mucioki, for being so positive and encouraging me to write this blog. I also would like to thank Hugh Beach, Lisbeth, Kerstin, Ellen Inga Kristine Haetta, as well as, Apmut Ivar and Sonja Kuoljok for teaching me about reindeer herding and letting me use photos taken by them or of them.

Notes

1The Sámi has been called Lapps which is a derogatory term and no longer in use. In English the name Sámi has been spelled in different ways – Sámi, Sami, Saami, and sometimes Saamis in plural –the same with the word sameby.

References

Barker, D. (2005) Beyond Women and Economics: Rereading “Women’s Work.” Signs. Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 2189-2209.

Beach, H. (1982) The Place of Women in the Modern Saameby: An Issue in Legal Anthropology. Antropologisk Forskning, Ymer (Svenska Sällskapet för Antropologi och Geografi), vol.102 :127–142.

…., (2000) The Sámi. In Endangered Peoples of the Arctic: Struggles to Survive and Thrive. Milton Freeman (Ed.) Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press

Collier, J. F. & Yanagisako, S. J. (1987). Introduction. In J.F. Collier & S.J. Yanagisako (Eds.), Gender and kinship: Essays toward a unified analysis. California: Stanford University Press.

Eikjok, J. (2004) Gender in Sápmi. Socio-Cultural Transformations and New Challenges. Indigenous Affairs: Indigenous Women, IWGIA(International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs), no 1-2, p. 52-57.

Kaiser, N., Näckter, S., Karlsson, M., Renberg, & Salander, E. (2015)Experiences of Being a Young Female Sami Reindeer Herder. Journal of Northern Studies. 2015, Vol. 9 Issue 2, p55-72. 18p.

Kuokkanen, R. (2009) Indigenous Women in Traditional Economies: The Case of Sámi Reindeer Herding. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2009, vol. 34, no 3, p. 499-504.

Olofsson, E. (1995) Samer utan samiska rättigheter och icke-samer med samiska rättigheter – en fråga om definition. (Master thesis, Lund University), published in the Northern Series, CERUM, Umeå University.

…..(2004) (2004) In Search of a Fulfilling Identity in a Modern World: Narratives of Indigenous Identities in Sweden and Canada. Published in the DICA Series (Dissertations in Cultural Anthropology), Uppsala University.

…..(2018) Inequality in Swedish Legislation of Sámi Reindeer Herding.In Global Currents in Gender and Feminisms: Canadian and International Perspectives. Glenda Bonifacio (Ed.) U.K.: Emerald Publishing.

Pehrson, R. (1964) The Bilateral Network of Social Relations in Könkämä Lapp District. Oslo: Norsk Folkemuseum and Universitetsforlaget.

Rosaldo, M. Zimbalist (1974) “Woman, Culture and Society: a Theoretical Overview”. In M.Z. Rosaldo, L. Lamphere & J. Bamberger (Eds.). Woman, culture, and society(Vol. 133). California: Stanford University Press.

Rönn, G. (1961) Sameland. Stockholm: Bokförlaget Aldus/Bonniers.

Schuurman, H. (director) (1974) “Sámi Herders” (Film) Montreal, National Filmboard of Canada.