Revitalizing native food systems and supporting food security through collaborative research in the Klamath River Basin

Revitalizing native food systems and supporting food security through collaborative research in the Klamath River Basin

By Megan Mucioki, Ph.D.

Our little Honda Civic was packed to the seams with our possessions and we said good-bye to my family in Ohio. My husband and I (plus our unborn daughter) were headed across the country to Orleans, California in the Klamath River Basin. Readied with no first-hand knowledge and the little information that the internet offered on our destination, we ventured off under-informed of the sheer remoteness, beauty, and wilderness that awaited us. The reason for our move- my recent hire as a post-doctoral researcher with the University of California at Berkeley. Only my appointment was not in Berkeley, it was at our field sites where I would be working as part of a collaborative research and extension team with three Native American Tribes in the area to shape a more sustainable and ecologically sound local food system as well as improve food security for tribal households in the region. I was thrilled and excited for this outstanding research opportunity in my field of study with a world-class research institution.

Our project team at headwaters of the Klamath River. This project, titled, Enhancing Tribal Health and Food Security in the Klamath Basin by Building a Sustainable Regional Food System, was funded by the USDA-NIFA-AFRI Food Security Program and led by PI Dr. Jennifer Sowerwine.

We rolled across the country with creeping anticipation of the novelty of a new home and job. Ironically, crossing stateliness into California over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, we encountered fresh snow and road restrictions which required chains in April. Given that California was in the midst of a severe drought, this was not something we were prepared for particularly in April. But alas we bought chains and carried onward. Our first stop was Berkeley for a few days to meet my new colleagues before we headed north to our permeant home. It was great to be in California and within a few days we finally arrived at our permanent home on the mighty and iconic Klamath River and her tributaries, a region home to vibrant Tribal communities with expansive Aboriginal Territories.

The Klamath and Salmon Rivers through the seasons near Orleans, California.

The majority of Californians (not to mention Americans) have little knowledge or experience with this part of the state. Although San Francisco or the Bay Area is termed “Northern” California, in reality there is a legitimate Northern part of the state that is under-recognized and appreciated. I always snicker on the inside when asked where we live. Cue me describing the area as “far North California, you know two hours from Eureka”, receiving a blank stare in return, and offering reassurance not to feel bad because most people are not familiar with the area. Although, many minds are sparked by the mention of Humboldt and adjacent counties (i.e. the Emerald Triangle), the largest cannabis producing region in the United States and revered by cannabis lovers for a quality product. Coined, the “green rush” with similarities to the gold rush during western expansion in 1850s, the local cannabis economy has skyrocketed the price of land, juxtaposing community and capitalism by attracting many outsiders with no concern for community and environmental health and leaving most tribal people with little hope of ever owning land in their homeland. Housing is a major challenge in the area, with many residents residing in campers or trailers, a crisis aggravated by the underlying distrust of outsiders given the booming cannabis industry and associated cash flow, steady flow of “trimmigrants” to the area in the fall, and a sizable population of questionable characters that remoteness and lawlessness attracts. As newcomers, it was quickly apparent we were not going to find anything too homie. Our only option was a single-wide trailer whose last occupants were the parents of our elderly landlords (you do the math J). We fixed it up as much as we could, moved in and called it home along with some unsightly rodents.

Our snow-covered trailer on Thunder Mountain. Residing 1,000 feet higher than the town of Orleans, we often received more snow than our comrades below.

A major challenge of living in this remote region is disconnection from grocery stores and health care services that are common place in most American towns. From our trailer on Thunder Mountain, it took two hours and ten minutes or 93 miles one way on a very windy road to get to a fully-stocked grocery store where we did most of our food shopping. Here-in lies the major reason why our research on local food systems and food security with Native Americans, one of the most vulnerable populations in the country, is so important. Considered a food desert by the USDA, this region is home to unique pockets of biodiversity and teeming with wild foods utilized and tended by local tribes. Historically, local tribes had access to some of the richest food sources, using fire and other forms of disturbance to cultivate tanoak acorn groves, open meadows of Indian potatoes, and patches of evergreen huckleberries, just to name a few of the 150-200 plant species used for food, medicine, and technologies by tribes in California. Tribes in the basin are closely tied to their tribal homelands, ceremonies, families, and native foods and fibers. However, lasting influences of tribal genocide and traumas of colonization, continued denied legal and physical access to native foods, and restricted rights to use fire as a management tool severely limits access to desired native foods. Today most tribal households depend on a mixed economy of hunting, fishing, or gathering native foods and store-bought foods.

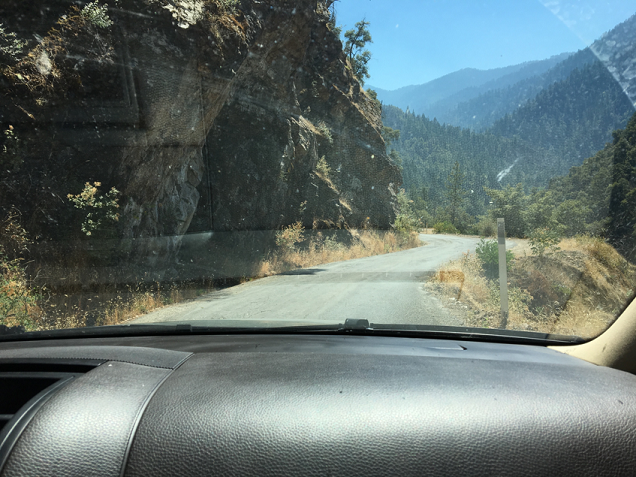

A sampling of the roads in the area- extremely windy, narrow, and edged by cliffs.

As we settled into our new lives, making extra-long grocery lists, swimming in the Salmon river, gardening, swatting mosquitos, and listening to lore and gossip from the locals, I started my collaborative research and extension work with local tribes. In the first year I traveled to various towns with tribal populations up and down the river conducting food focused focus groups and key-informant interviews. I also began work with colleagues at the Karuk Department of Natural Resources to develop an herbarium to be housed at the Tribe’s museum.

Ben Saxon, of the Karuk Department of Natural Resources, shows off a Pacific Dogwood voucher specimen to Dr. Tom Carlson.

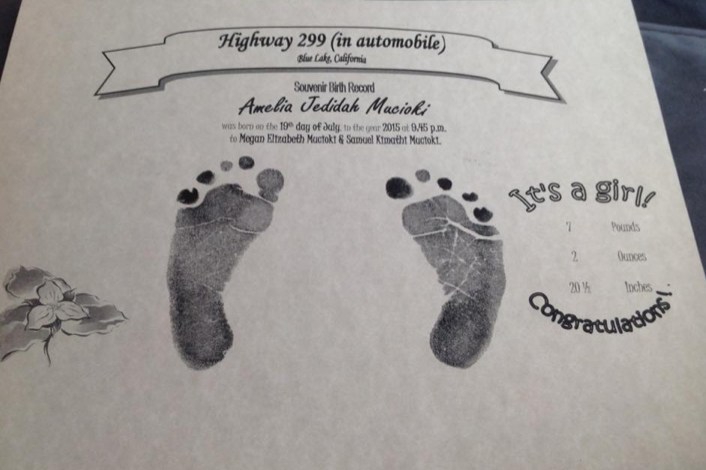

Very pregnant by the time of the last focus group, on July 19, 2015 my daughter was born. Many women in the area have home births, but I felt ill-equipped and under supported to do so after moving to what was still an unfamiliar area for me. The night before her birth, my husband and I came home from our friends and I perused social media before going to bed, glimpsing a viral video of a women delivering a ten-pound baby in her car. My husband chided me for watching such a thing with our own delivery so close. Little did I know at the time, I would go into labor the next evening. Dashing to the hospital two-hours away, I had the feeling we would not make it. Much to my doctor’s surprise, I arrived at the hospital holding my, thankfully healthy and breathing, daughter, who I delivered 30 miles earlier while my husband sped to the hospital. It is a memory I will never forge.

My daughter’s “Souvenir of Birth” from her birth on highway 299.

As our daughter grew through her baby months, I collected herbarium voucher specimens, conducted more interviews, and analyzed data. Months turned to years and life on the river was as exceptional as it was unique and as challenging as it was peaceful. We often found ourselves without electricity or water, snowed in, rained in, obstructed by rock slides, or experiencing wild-fires with dense smoke depending on the season. The need for local and sustainable food systems, Indigenous led management of forests, grassroots health collectives, and real action to combat climate change is never so real or apparent than in everyday life of residence on the river. People rallied around food and resilience, working as individuals and a community to garden, preserve, gather, hunt, and fish and store food for the harsh winter months as well as safeguard the community from fire and catastrophe with local efforts. Including carrying out cultural and prescribed burns, honing and training a locally manned fire and rescue team, and constantly fundraising through to fund important youth and community endeavors.

Our forthcoming publications highlight food-related challenges and food security vulnerabilities of tribal people living in the Basin. Our research documented higher rates of food insecurity (in general) and severe food insecurity (i.e. reducing size of meals and/or skipping meals) in tribal households in the Basin than any other population in the United States1. While reliance on Federal food assistance programs is high, there is a strong demand for better access to native foods through more hunting, gathering, and fishing enabled by removal of law and policy restrictions and Tribal led forest and river management2. Many tribal people report using food assistance programs because viable populations of their preferred native foods are no longer available or accessible to them due to decades of forest and river mismanagement and legal and economic restrictions2. Relationships with native food and fiber plants play a pivotal role in Native American health and wellbeing beyond nutrition and sustenance3, with many extension and education opportunities during our 5-year project working to support plant-people relationships in tribal communities in the Basin (as well as connection to hunted and fished foods).

A collage of photos from food focused workshops during our 5-year food security project.

After three years of living on Thunder Mountain, this past spring we made the hard decision to move north to a larger town for better housing and more opportunities for our daughter. Our team recently received a second USDA grant to continue work together. Our most recent work focuses on increasing the resilience of cultural food and fiber plants in the face of climate change in Karuk Aboriginal Territory, titled- Karuk Agroecosystem Resilience and Cultural Foods and Fibers Revitalization Initiative: xúus nu'éethti – we are caring for it. I currently enjoy the luxury of grocery shopping in an hour rather than a whole day as well as traveling back to our field sites in Karuk Aboriginal Territory, a road that holds so many memories and milestones formative to my personal and professional development during an exceptional three-years on the river that we called home.

Megan Mucioki, Ph.D. is a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at the University of California at Berkeley. Megan’s research engages Indigenous and rural communities in food and seed focused research that informs the in-situ conservation of traditional food plants and explores relationships between access to traditional foods and household seed and food security. For more information on the collaborative research and extension projects Megan is a part of visit: https://nature.berkeley.edu/karuk-collaborative/

NOTES:

1. Sowerwine, J., Mucioki, M., Sarna-Wojcicki, D., and Hillman, L. (forthcoming). Reframing food security by and for Native American communities: A case study among Tribes in the Klamath River Basin of Oregon and California. Food Security.

2. Mucioki, M., Sowerwine, J., & Sarna-Wojcicki, D. (2018). Thinking inside and outside the box: local and national considerations of the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR). The Journal of Rural Studies, 57, 88-98.

3. Mucioki, M. (forthcoming). Gathering is surviving now and long into the future: plant-people relationships in Klamath River Basin of Northern California and Southern Oregon. Human Ecology.