On returning to your academic roots, and propagating them

On returning to your academic roots, and propagating them

By Ashley Glenn

Doctoral and postdoctoral research takes us out of our comfort zone and into new worlds. It’s an intellectual adventure: stimulating and absorbing, connecting us to the richness of the world, to new methodology and fields of study, and the future of research. It’s consistently challenging and often frustrating. It’s that adventure that Natalie Mueller and I are in the middle of, Natalie as an archeologist doing horticulture-intensive research, and me as a botanist in the middle of anthropology-intensive dissertation writing. When she asked me to join her to teach at an NSF Research Experiences of Undergraduates (REU) hosted by the Center for American Archeology, I saw a much needed break from writing to get out in the countryside, and jumped at the chance.

Students participating in the summer 2018 NSF-REU: "Long-term Perspectives on Human-River Dynamics at the Confluence of the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers," on a field trip to Emiquon Nature Preserve. Follow the link to apply for next summer! Upper row from left: Natalie Mueller (instructor), River Fuchs, Kathryn Kuennen, Blaine Burgess; Bottom row from left: Dana Mineart, Wendi Wingerson, Monica Corley, John Jadrich, Morgan Tanner, and Josh Raymond (instructor).

I put away my dissertation for the week and loaded up my car with botanical field guides, plant presses, and my field-happy puppy, ready to get back to my academic roots. My task was to teach a group of anthropology undergrads the basics of botany. My partner was Natalie Mueller, tasked with teaching them the basics of paleoethnobotany. Together we would bring them through the basics of ethnobiology. Our goal was that no matter what their path, they would have a foundational understanding of the uses and needs within these overlapping studies, and emerge with a strong methodology toolkit after this summer intensive research experience.

Our students in an original settlers cabin preserved at the McCully Heritage Project, Calhoun Co, IL.

Driving up from St. Louis, I left the urban landscape through the stretch of river towns, casinos, wineries, and tourism north of the city, ending up in the peninsula formed by the confluence of the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. This land of floodplains, “hollers”, and bluffs, with white wooden houses, general stores, and fields of Midwestern summer flowers made me feel like I was travelling not just two hours north, but back in time.

Sunrise over the Illinois River in Kampsville, IL.

The Center for American Archeology is a place like no other. Established in 1953, it sits in the small town of Kampsville, IL, and occupies existing structures: houses, shops, sheds and schools. Living amongst ancient artifacts, Victorian houses, midcentury furniture, and modern research equipment gives this place a timeless, dreamy quality and a sense of connection to the flow of science. We wake up at sunrise and work well into darkness, just as I imagine the people who created the artifacts, the people who first lived in the houses, and the people who built the Center did.

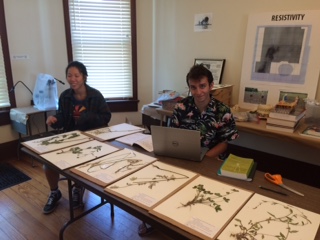

Teaching the students how to identify plants and make voucher specimens.

This stretching back in time extends to our work there: Natalie and I are going back to the first things we learned in our fields, and teaching them to the next generation of researchers. Our students are eight bright students from around the country, all coming here for different reasons, and all looking towards different academic paths. We began the lesson with the building block of botanical data: the herbarium specimen. We strolled through the tiny town, examining anatomy through the old trees and plantings around us. We collected a few plants, and pressed them on site. We walked them through identification, and spent some time on the dynamic and subjective nature of plant taxonomy. The students saw how to create a good herbarium specimen and why we create voucher specimens when researching and publishing about plants. We covered the ways that herbarium specimens inform data for many fields from conservation to climate change, and how comprehensive collection data can make your specimens beneficial beyond your own projects. After a good foundation, we went to a scrubby field near a cemetery and collected everything in flower. Mid-July in the Midwest hit them hard – while Natalie and I pressed the flowers back at the house, we commiserated with our students with stories about extreme heat and insect attacks that are trademarks of our careers.

Part of learning how to go plant collecting is learning to do a proper tick check afterwards!

McCully Heritage Project Director Michelle Berg Vogel teaching the students about conservation and agroforestry.

After seeing the result of proper (and some improper) collection, identification, and pressing, we were led on an amazing tour of useful plants and ecology at McCully Heritage Project, and collected an extensive botanical flora. The students took the helm at identifying and pressing the collection, and did a remarkable job.

Two of our fantastic students with their finished specimens.

We finished up my time in Kampsville with traditional knowledge and medicinal plants. We covered local and global perspectives on plant use, ethics in research and respect in the field, and the limitations of science in understanding both the chemistry and history of medicinal plants. We made herbal insect repellant and my favorite fieldwork salve. It couldn’t have come sooner – we are all covered in bites, scratches, and irritation by that point!

Learning how to make salves from medicinal plants.

With my botanical bases covered, I returned to the city and my own research, while Natalie brougt them through the foundations of paleoethnobotany, using the Center’s extensive collections. A week later, I met them at the Missouri Botanical garden herbarium to see botany in action, to see how the research they conduct can enter a huge stream of botanical and ethnobiological knowledge that stretches around the world and through centuries.

Touring the maize collection at the Missouri Botanical Garden Herbarium.

We also visited an urban farmer’s market. It was a familiar setting to many of them, but gave them an introduction into the type of ethnographic and botanical data we create through market surveys.

Two of our students conducting surveys at the Tower Grove Farmer's Market in St. Louis.

To watch these students go from asking simple questions about plants to drawing sophisticated conclusions about botanical research was inspiring. It brought me back to my undergraduate days, how the fields and plants around me grew richer with every class, and how my imagination was given more and more to grab on to and explore. For me back then, and for these students it was an expansive experience, and opening to possibilities.

Enjoying some beers with the other instructors, and keeping an eye on the plant dryer / fire hazard / haunted house prop.

For me as the teacher is was easing- a comfortable return to the methodology I began with, and the knowledge I hold most deeply in my academic story. For Natalie as well: evenings after lectures were spent sharing a beer on the porch, reminiscing about our own beginnings and how our early experiences with field schools shaped our paths. For two researchers deep in post doc and PhD research, forging new paths, it was a comfortable, fortifying, and confidence-raising homecoming.