Green Islands for All? Avoiding Climate Gentrification in the Caribbean

Green Islands for All? Avoiding Climate Gentrification in the Caribbean

Hurricane Irma turns the Caribbean brown. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, September 11, 2017.

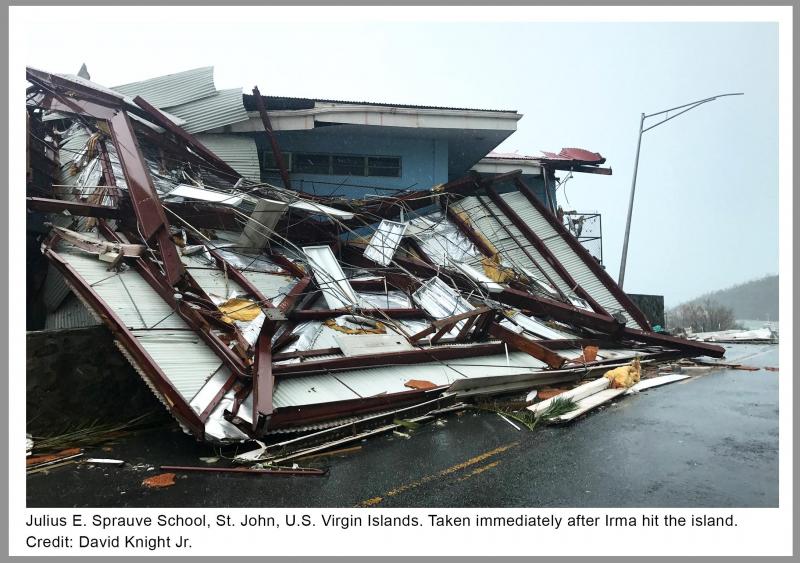

Hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated many Caribbean islands, where vulnerable communities now find themselves on the front lines of a climate crisis. As we saw post-Katrina in New Orleans, we are witnessing mass displacements of people, including the evacuation of an entire island. Each affected island is a disasterscape, a term Anu Kapur (2010) uses to describe the collective condition of disaster, places with “a gaping wound that pleads for quick repair and relief.” As communities struggle to regain a sense of stability, governing bodies and interested parties make plans for the future. In the Caribbean, these post-disaster proposals include urgent calls to rebuild the Caribbean in a “green” framework. Resiliency is one primary goal, which aims to improve the capacity of islands to recover better from future hurricanes. For example, the Governor of the US Virgin Islands, Kenneth E. Mapp, has established the USVI Hurricane and Resiliency Advisory Group “to make critical infrastructure, homes, and businesses more resilient to future storms and other natural disasters” (Oct. 16, 2017). Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit of Dominica also made an urgent call for resiliency in a poignant speech before the U.N. General Assembly:

Let these extraordinary events unleash the innovation and creativity of global citizens to spark a new paradigm of green economic development that stabilizes and reverses the consequences of human-induced global warming. (Sept. 23, 2017)

Across the Caribbean, there are many ready to ignite these sparks. Richard Branson, who owns Necker island in the British Virgin Islands, began talking about re-developing the BVI with renewable energy less than a week after Maria. The Governor of Puerto Rico, Ricardo Rossello, recently entered into conversations with Tesla to discuss rebuilding with solar power. Virgin Islands Senator Janette Millin Young has just announced that her staff is working with Tesla’s SolarCity to create a plan for the U.S. Virgin Islands. The day after Maria hit the US Virgin Islands, a realtor with investments and/or interests in the islands suggested to a public facebook group that it is “never too soon to start thinking about rebuilding our tourism, cruise ship, vacation rental & second home markets. . . . [a]s we rebuild we reposition the USVI as a "solar showcase" for companies searching for the perfect place to demonstrate what their products can do.”

Renewable energy is, of course, a critical and necessary component to address the climate crisis. But will green energy provide just and equitable solutions for Caribbean people? Whose voices are at the table making decisions about energy use and distribution? Will everyone have an opportunity to benefit from what Richard Branson calls the “Marshall Plan for a greener, resilient Caribbean”?

Kapur explains that “diasterscapes” become commodities that can be sold, politicized, and corrupted. Re-building green may strengthen the islands to better withstand future storms and help reduce environmental impact. But it is also the case that after climate change disasters, low-income and/or communities of color often cannot afford to rebuild. Prime lands are sold to wealthier occupants who develop properties for their leisure and profit, often at the expense of the surrounding communities. Here the concern is “climate gentrification.” As Darwin Bondgraham (2007) points out in his analysis of New Orleans after Katrina, natural disasters often exacerbate pre-existing power dynamics and gentrification processes. We wonder who will be able to return and what will become the “new normal” of the Caribbean as the islands embark on the long, challenging and expensive recovery process?

We also need to consider whether “resiliency [is] being coded as a way to do the land grab,” a point raised by David Capelli, founder and CEO of Florida smart city consultancy TECH Miami.

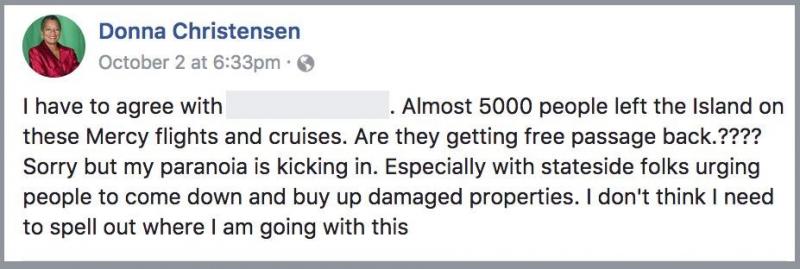

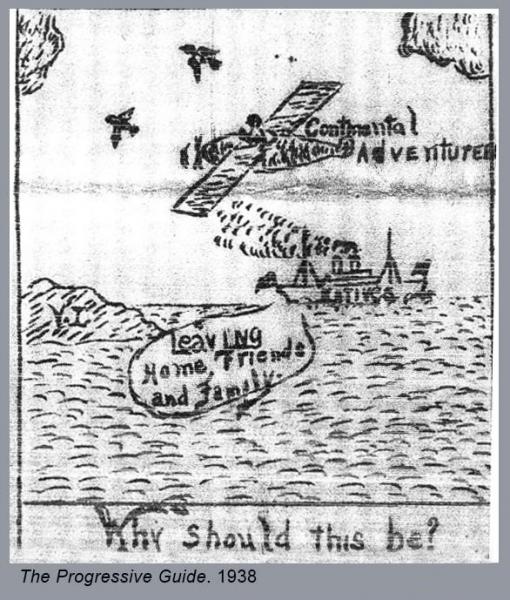

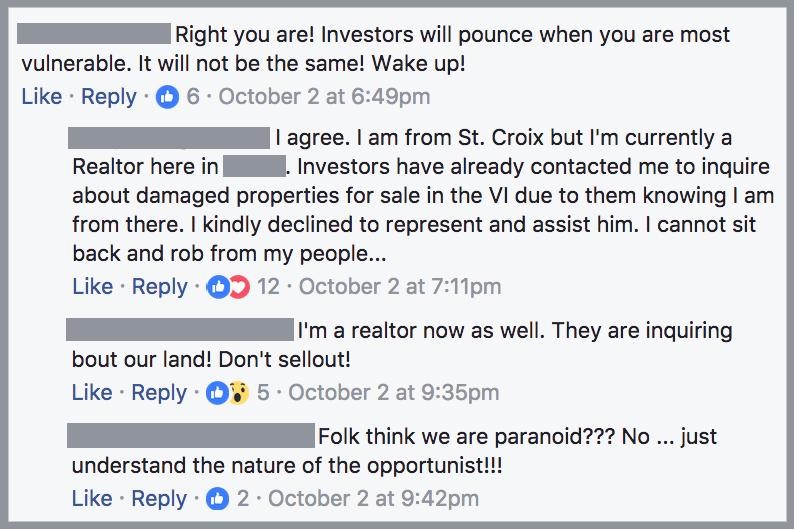

Fromer VI Delegate to Congress, Donna Christensen, highlighted her concerns about this in a recent social media post about who is leaving, arriving, or returning post-hurricanes. It is not the first time Virgin Islanders have asked this type of question. In 1938, as people from the continental United States began moving more frequently to and purchasing property in the islands, a political cartoon appeared in a local paper, asking why natives were leaving home, friends, and family as continental adventurers flew by overhead en route to the islands.  Christensen apologizes for paranoia, but she is, of course, justified. In just one example, stateside Virgin Islanders working as real estate agents are already receiving calls asking whether or not any cheap land is available. The callers, who are planning to capitalize on the disaster, probably know that many of the displaced will not have the capital to rebuild.

Christensen apologizes for paranoia, but she is, of course, justified. In just one example, stateside Virgin Islanders working as real estate agents are already receiving calls asking whether or not any cheap land is available. The callers, who are planning to capitalize on the disaster, probably know that many of the displaced will not have the capital to rebuild.

These calls illustrate one of Darwin Bondgraham’s key arguments: after natural disasters, economic elites can monopolize the planning process and rebuild in ways more amenable to accumulating capital. This could as easily be the case with renewable energy and ecotourism as it has been with traditional electric grids and sun and sand tourism. In Barbuda, there was a mandatory evacuation of the entire island of 1,800 people. Subsequent press described the island as “deserted,” “empty,” and “literally rubble” with visions of feral pets and abandoned livestock. All of these images paint a picture of a forgotten tropical landscape, one that is up for grabs. Yet, the evacuated people of Barbuda were having townhalls with the Prime Minister of Antigua where many were fighting to go home to clean up and rebuild - and return to their animals.

This rhetoric of “paradise lost” recalls the settler environmentalism that La Paperson (2014) describes, a “terra sacer...sacred/accursed lands...wastelands ripe for rescue by environmental [and capitalist] settlers.” Barbuda’s common land is at stake when the Prime Minister cites a cost of $200 million to rebuild when the average home does not cost more than $50,000. A call to privatize the commonly owned land catalyzes an increased reliance on loans and leaves the island vulnerable not only to the capitalist development that has plagued much of the Caribbean, but to predatory lending practices that often target communities of color.

This rhetoric of “paradise lost” recalls the settler environmentalism that La Paperson (2014) describes, a “terra sacer...sacred/accursed lands...wastelands ripe for rescue by environmental [and capitalist] settlers.” Barbuda’s common land is at stake when the Prime Minister cites a cost of $200 million to rebuild when the average home does not cost more than $50,000. A call to privatize the commonly owned land catalyzes an increased reliance on loans and leaves the island vulnerable not only to the capitalist development that has plagued much of the Caribbean, but to predatory lending practices that often target communities of color.

To mitigate this, resiliency groups must include people who examine questions of race, class, gender, and power in their environmental advocacy. As U.S. Virgin Islands Senator Janelle Sarauw also stated, millennials deserve to be a part of the decision making process. We must carefully consider who will get a seat at the table. Kilan Ashad-Bishop, who sits on the City of Miami’s Sea-Level Rise Committee, specifically as an advocate for the city’s low-income communities, and the Fondes Amandes Community Reforestation Project provide two models of environmental advocacy that consider the needs of a wider cross section of people. The NAACP’s Environmental and Climate Justice (ECJ) Program is another example; they press for community-owned energy and initiatives that create clean air, clean energy, and economic justice for all. We can learn from these approaches that link development with environmental justice. We can also draw upon research at the Natural Hazards Center about how to best design participatory recovery processes following disasters.

Perhaps, this is an opportune time to propose an economics that eschews neoliberalism and centers the advancement of the collective rather than lining the pockets of a few. A cooperative model is worth considering, where collectively owned land and industry allows the people to make collective decisions about (re)development and foreign investments on their Caribbean islands. There are several examples of this. The St. John Heritage Collective of the U.S. Virgin Islands is an emerging non profit that aims to preserve the identity and culture of the people of St. John through land preservation, grassroots community organizing, and community directed development. For example, small scale farming cooperatives could require that the hospitality industry purchase a certain percentage of locally grown food. Barbuda was once known as the “breadbasket” of Antigua because of tomatoes, melons and other crops that supplied Antigua during and post enslavement. Educational cooperatives would require that foreign investors contribute to modernizing schools and libraries. Cooperatives can help protect the agricultural and natural heritage of the Caribbean, including its unique flora and fauna. The post-hurricane fate of the magnificent frigatebirds in Barbuda remains unclear as they usually fly out to sea to avoid a storm.

We must advance the cultural and economic quality of life for ALL CARIBBEAN peoples. In addition to new economies, a successful Caribbean redevelopment project would need to feature an intersectional environmental justice movement, one that centers questions of ecological sustainability around the needs, experiences,histories and ideas of the most vulnerable people in society. “Green Islands for All” asks us to take up Sylvia Wynter’s (2003) call to challenge our prevailing conceptions of what it means to be human in this world. Specifically, we must be human in ways that are not defined by the overrepresented logics of whiteness, neoliberalism, and predatory capitalism. It is also a call for a pedagogy or framework that allows us to critique the historical settler colonialism and contemporary settler environmentalism and centers a decolonizing approach to (re)development.

Moving forward, an environmentally just rebuilding calls attention to two questions. 1. How do the forces of structural racism, white supremacy, and colonialism make Caribbean people particularly vulnerable to natural disasters and the redevelopment projects that emerge in their aftermaths? 2. How can we decolonize environmental practices so that the voices of marginalized people are central rather than peripheral in the movement for ecological sustainability?

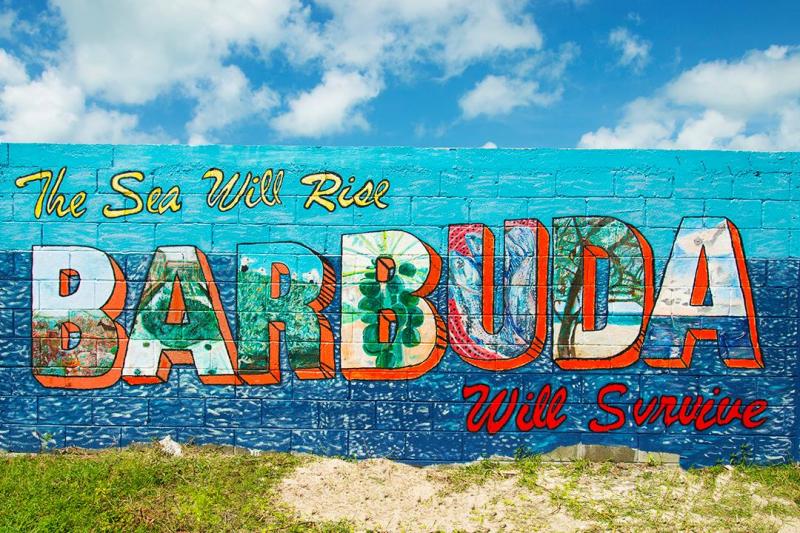

Barbudan students worked with Artist in Residence Noel Hefele at the Barbuda Archeological Research Center in 2014 to create this mural. It survived Hurricane Irma. Photo Credit: Mohammid Walbrook.

Published October 19, 2017

AUTHORS

Jennifer D. Adams is an associate professor at the University of Calgary and researches science teaching and learning with an emphasis on informal, place-based science education from a critical, social-justice perspective. Her current research focuses on the link between creativity and science teaching and learning in order to advance diversity of peoples and perspectives in science. She is also affiliated with the Barbuda Research Complex where she does work on science learning and sustainable resilience.

Crystal Fortwangler is a former professor of sustainability and environmental anthropology, and is now produces films that promote social and environmental justice. She also explores how non-human animals fare in the Anthropocene. Her recently released film, It Ain’t Easy Being Green, documents the struggle to protect crops and iguanas at the same time in the U.S. Virgin Islands. After recent hurricanes hit the U.S. Virgin Islands, where she has conducted research for two decades and more recently pursuing film, she is focusing now on merging her academic expertise with filmmaking to highlight the intersections of the climate crisis and social justice.

Hadiya Gibney Sewer is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Africana Studies Department at Brown University and a part time professor at the University of the Virgin Islands. Her research interests include Africana feminism, Western empires and Caribbean subject formation, Caribbean philosophy, and radical political thought. She is a staunch critic of American colonialism in the U.S. Virgin Islands and a co-founder of the St. John Heritage Collective.

Comments (2)