Fellowship Profile Series 2: Blaire Topash-Caldwell, 2015 Indigenous Ethnobiologist Fellow

Fellowship Profile Series 2: Blaire Topash-Caldwell, 2015 Indigenous Ethnobiologist Fellow

Starting in 2015, the Society of Ethnobiology began supporting three graduate research fellowships. This series includes short essays profiling the research by each of the fellows during the year that they received funding.

Blaire Topash-Caldwell, 2015 Indigenous Ethnobiologist Fellow

Words: Blaire Topash Caldwell

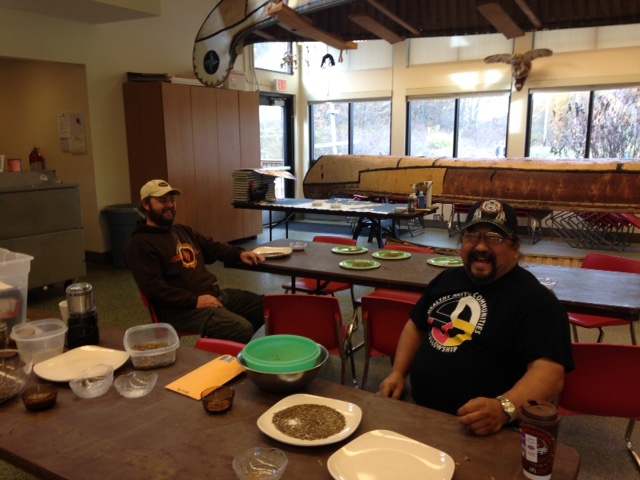

During my research visit I traveled to Grand Rapids, MI and visited the Goodwillie Environmental School. While there I interviewed a representative from the Great Lakes Lifeways Institute. In partnership with the Institute, I was also able to interview a tribal member from Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians who is an expert in wild rice production and the Rice Chief for his community. Additionally, I conducted interviews in my own tribal community with professionals from both the Department of Natural Resources as well as the Department of Language and Culture. While I originally intended on centering much of research on the spread of the invasive species, the emerald ash borer, on tribal lands, I was surprised to learn that this was one of many invasive species that tribes in the Great Lakes must contend with such as swans which have an adverse effect on indigenous waterfowl. I also learned of the multiplicity of other tribally-based natural resource management initiatives taking place in the Great Lakes region. For instance, what seemed to be more important and pressing to tribal members with whom I spoke were tribally based natural resource management initiatives such as the re-meandering of rivers and streams in the area as well as the role of traditional ecological knowledge in mitigating the environmental issues that standard practices could not address. At the center of these discussions was wild rice production in terms of both environmental and corporeal health.

At the conclusion of my visit my findings altered my research focus toward the emerging importance of water, other tribally-based natural resource management initiatives such as re-meadering and the relationship between traditional foods like wild rice and the health of the larger Native community in the Great Lakes. As I continue transcribing my interviews and conducting follow-up interviews, I hope to organize my findings in an article to be considered for publication in the Journal of Ethnobiology in early 2016.

Comments (3)