Evergreens for the darkest days: The ancient roots of Christmas trees

Evergreens for the darkest days: The ancient roots of Christmas trees

The Christmas tree has always been especially revered in my family. The seriousness of our yearly ritual was instilled by my father, who is a tyrant on all matters tree related. My mother tells the story of their first Christmas together, normally a blissful event for newlyweds, when my father became apoplectic over my mother’s indiscriminant tinseling of the tree. With a mad gleam in his eye, he ranted: The individual strands of tinsel were meant to symbolize icicles, but, as my mother had haphazardly strewn clumps of tinsel that did not hang down neatly in the manner of icicles, the tree was now a parody of its true majestic self! My mother came from a large family of tinsel-globbing, unwitting tree desecraters. Rather than try to meld their inherited visions of the ideal Christmas tree, she opted for peace and vowed never to let tinsel pass our doorstep again.

Mom and Dad, having worked out their Christmas tree differences over the course of 35 years.

Despite this wise measure, the decorating of the Christmas tree was not to be approached lightly or without proper initiation by my sister and I. Every year, Dad carefully places each light, attending to the patterning of their colors, and the way they are hidden within yet illuminate the branches, misty-eyed, singing along to O Tannenbaum with feeling. My father received this attitude toward the tree from his own father, who was likewise fastidious and particular in his observance of the tree decorating ritual. An engineer and ingenious tinkerer, Gramps reportedly approached decorating the tree as a private meditation or artistic endeavor – no kids allowed. I imagine his son imbibed this veneration of the tree in lieu of the fun most kids have tossing tinsel, and in turn I have also inherited it.

My tree, and my little helper, this year.

It may be mere coincidence that a peculiarly strong tree devotion traveled down to me through my one German grandparent, but by all accounts the Christmas tree has very ancient roots in Germany. Though they weren’t widely known in England or the United States until the 19th century, there have been Christmas trees in more or less their current form in Germany since at least the 1500s. But the Christmas tree’s origins are centuries, if not millennia, older. Since I became an ethnobotanist, I’ve been learning a little bit more about the history of my favorite ritual every year, and I’ve discovered that the Christmas tree is a powerful and very old symbol of protection and rebirth. If you’re interested in this history, a great place to start is with Christian Rätsch and Claudia Müller-Ebeling’s 2006 book Pagan Christmas: The Plants, Spirits, and Rituals at the Origins of Yuletide. This fascinating historical ethnobotanical study of Christmas covers everything from incense, to golden apples, to the Erotic Bean Fest, and, of course, the tree.

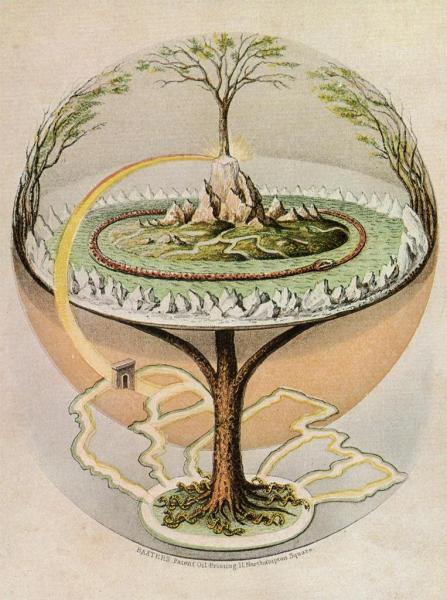

Engraving of Yggdrasill, the Norse world tree, by Richard Folkard 1844, after Finnur Magnusson's illustration of the World Tree of the Edda, 1825. Courtesty of Artstor.

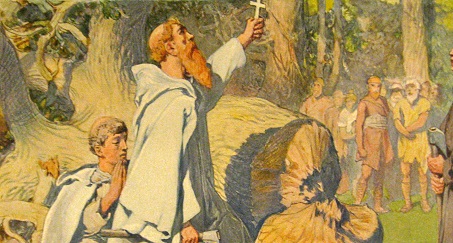

The Christmas tree is one of thousands of symbolic descendants of the archetypal world tree, the tree that connects the Sky, the Earth, and the Underworld. Rätsch and Müller-Ebeling write “Anyone who looks closely at the threshing floors of old Black Forest houses can often see the magic numbers scratched upon them and may also see a tree of life, in the form of a fir or spruce branch. The same symbol can be found in old churches. Beneath an abstract image of a Christmas tree, there are three horizontal steps, representing the shamanic staircase to the sky and the world tree…” Ancient Northern European peoples worshipped trees of all kinds, from the Norse Yggdrasil, a mythical ash and the literal world tree, to specific living trees like Thor’s oak, which was considered sacred by pagans in what is now Hesse, Germany until it was cut down by Christian missionaries in the 8th century AD. Early Christians in Europe destroyed sacred trees and groves systematically, but there were some who advocated a different approach. As early as the 4th century AD, St. Augustine wrote “Do not kill the heathens – just convert them; do not cut their holy trees – consecrate them to Jesus Christ.”

Saint Boniface cuts down Thor's Oak, while the Germanic Chatti tribe look on in horror. By Emil Doepler, 1905. Coutresy ofWikimedia Commons.

The fir tree also held a special significance associated with the darkest days of the year: it was a spiritual protector. The great 12th century AD German scientist and Catholic saint Hildegard von Bingen wrote “Wherever the fir wood stands, the sprits of the air hate it, and shun it. Enchantments and magic spells have less power to effect things there, than they do in other places.” What spirits of the air could this Benedictine nun possibly have been referring to?

Odin's Wild Hunt. By Peter Nicolai Arbo, 1868. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What are now known as the 12 Days of Christmas were once considered a very dangerous time, when Odin and his hunters rode through the sky, hidden behind winter storm clouds. Odin, the Germanic god of wisdom, death, and frenzy, among other things, is one of a bevy of Christian and pagan mythic contributors to our Santa Claus (Odin’s mid-winter wild hunt even has him cavorting with a mob of elves in some tellings). To ward off misfortune during these dark and dangerous nights, people smudged their houses with fir resin and other aromatic plants. This pagan tradition, too, was later embraced by Catholic priests and is still practiced in some parts of Scandinavia today. Having just learned this history, the warm, peaceful feeling I got when I opened my front door today and smelled my Christmas tree took on a whole new significance – ancient people believed this smell protected their homes from the destructive magic of mid-winter nights.

My fruit decorations.

Evergreens were powerful symbols of rebirth at the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. Despite her arguably poor tree etiquette, my mother was the parent who taught me the significance of the winter solstice. A summer-loving soul, she has always found the winter solstice to be cause for celebration, even though in our western New York home it is followed by at least three more months of snow and cold. The ancient people who started our Christmas tree tradition agreed. The winter solstice marked the rebirth of the sun, and with it the fertility of the Earth and everything on it. The earliest Christmas tree decorations were fruits, nuts, and flowers, which invoke fertility, and candles and tinsel (yes, tinsel, Dad!), which symbolize the return of the sun. The ritual of decorating the home with evergreen boughs and symbols of fertility at the winter solstice seems to have been passed down, more or less unchanged, from pre-Christian Europeans, however the tradition of decorating the tree has probably changed significantly since then.

Hints of green at the Roy H. Park Preserve, near Ithaca, NY.

Decorating trees was such an important part of pre-Christian religious practice in Northern Europe that the 4th century AD Roman Emperor Theodosius the Great felt the need to outlaw the practice, but people probably weren’t going out and cutting down Christmas trees. It stands to reason that people who worship trees would not approve of cutting them down for non-essential purposes, and there aren’t records of trees inside of houses until the 1500s. Reading about all the tree decorating and venerating that took place outside made me want to go for walk in the woods on a snowy day, so I did. The dominate evergreens in the forests around my house are hemlocks, not firs, but I could still get an idea of why my ancestors chose to honor evergreens at this time of year. Looking out at a landscape of blue, white, and grey, the groves of hemlocks are the only source of sweet green relief for the eye – even more so when they are shining in the sun. Walking in the relative warmth and stillness under their branches, I could also see how they might be perceived as protectors from the spirits of winter.

Making seed ornaments.

When I finished writing this last night, I had the urge to add some traditional offerings to my Christmas tree. I’m not very crafty, but I do have a lot of seeds in the house – my personal favorite is the wasabi pea bulb, but they all have their own special charm. You can also cut up oranges and apples (put some lemon juice on the latter) and dry them out in your oven – they look great when illuminated from behind. If your dog likes apples as much as mine, though, hang them high.

Wasabi pea and coffee bulbs!

The Earth is especially in need of our veneration and encouragement to keep on turning this year. For all those working to protect the trees and other creatures, thank you! If you have trees on your mind after reading this, consider contributing to the Nature Conservancy (some of their benefactors are matching donations through the holiday season), another advocacy group, or a community that is struggling to protect the land.

Happy solstice!

By Natalie G. Mueller, Forage! co-editor

Comments (4)