Ethnobotanist Faced with Yard Nazis, Does Ethnography

Ethnobotanist Faced with Yard Nazis, Does Ethnography

Sometimes, you can fight city hall. Ethnobiologist Myrdene Anderson discusses lawsuits, public action, and withcraft in her long fight to keep her lawn wild in West Lafayette, Indiana.

I've lived for 40 years in West Lafayette, Indiana, as an employee of Purdue University. Since buying a home and a yard in 1980, neighbors had been filing complaints about my natural landscaping without my knowledge until I received the first summons from the City, in 1988. I didn't respond, as I was traveling, although I did later meet with a city official at the property (with my witnesses). The official first mentioned "different cultural values", presumably between myself and the complaining neighbors, then conceded that the yard was my property. Inspectors and the city attorney would not have agreed!

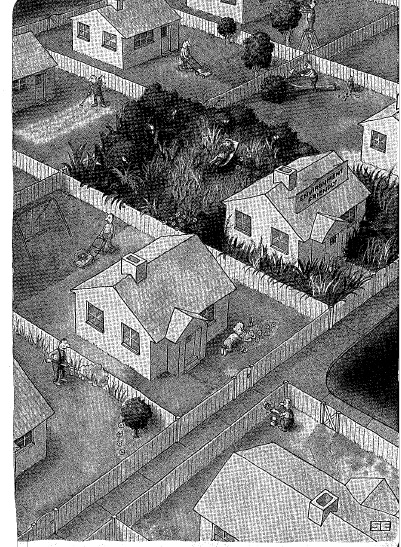

The Author's lawn, in context, from Google Street View.

Only after a second summons in fall 1989 did I learn that back in July of 1988, while I was attending my father's funeral on the west coast, there had been an inspection of my property. I and my yard were found in supposed violation of codes with maximum penalties of $500 per day, accumulating to $216,000 in 1989. I had purchased my house for $40,000, approximating its assessed value.

When the second summons showed up in 1989, I engaged a prominent attorney. We met each other at the courthouse, whereupon my keenest ethnographic skills did not suffice to figure out what was going on, except that it seemed my attorney was taking the city's side in urging me to sign a consent decree. Repeatedly, I refused to put my signature to something amounting to promising to stop beating one's wife. I wandered home in a daze. Shortly thereafter I inquired of another attorney, who had been a city attorney, whether more was required of me., "Let sleeping dogs lie," he shrugged.

"Environmentally Firendly" Lawn, from The New Yorker

In mid-1990s, the City again pounced, nudged by an undated petition copied below:

By this point the fine should have exceeded a million dollars, although the City had ceased mentioning any fines. This time the City also charged me with contempt of court, because my 1989 attorney had, without my permission or knowledge, signed the consent decree; he had also, alas, meanwhile died. The envelope containing that document sat unopened in a drawer during the intervening years because I thought it was another bill for services that I was determined not to pay. The second attorney I had consulted, opining that I should "let sleeping dogs lie", was immune from questioning as five years had passed.

We, residents of neighborhoods on the east and west sides of Northwestern Avenue, are very concerned about the following conditions at [my house].

- the physical condition of the house is deteriorating, while other owners in the neighborhood are improving their homes and properties

- the front yard is not compatible with other yards in the neighborhood; it appears to be a jungle and obviously violates West Lafayette codes for proper yard maintenance

- The possibility of fire and the difficulty the fire department would have getting to the fire given the condition of the property surrounding the house; such difficulty represents a direct threat to lives and other properties in the area

- The existence of rats and other rodents, which have increased in the neighborhood as conditions at 1807 have deteriorated; such animals are a potential health hazard

- The safety of neighborhood residents who have fallen on the property as a result of conditions in the front yard (a public right of way) and who now carry flashlights at night to protect themselves from rats and other rodents near the property

- The animal excrement which is a breeding grounds for flies, mosquitoes, and other insects which adversely affect other properties in the area

- The harmful effects this property has on the value of all other homes in the area

[signed by 68 neighbors (36 of them evident spouses), all within six blocks or so of the property in question]

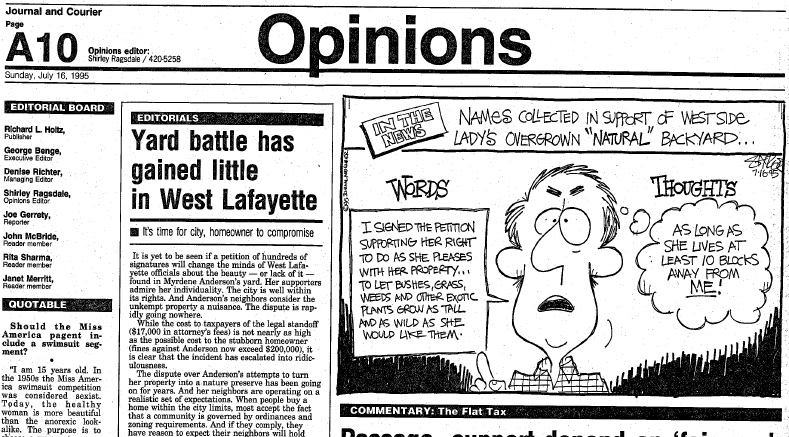

Profile from West Lafayette's Community Times

However, this time I had found a third attorney—with difficulty because the several others I approached each had conflicts of interest. (I still retain this attorney, whom eventually I could "pay" with Red Cross pins and paraphernalia collected around the world.) Persons I scarcely knew made placards and drew cartoons in support of my position, and some people actually gave me money for the mounting attorney costs. An attorney whom I had never met had started a petition which was prominently placed in both West Lafayette and Lafayette:

PETITION IN SUPPORT OF MYRDENE ANDERSON'S NATURALISTIC GARDEN

We, the undersigned, support Myrdene Anderson's approach to naturalistic gardening and applaud her creation of an environmentally friendly haven for wildlife and flora. We find the verdance of her yard to be a celebration of life which is infinitely preferable to the traditional sterility of an expanse of manicured turf with heavily pruned foundation shrubbery. Her no-chemical-input gardening is both medically and environmentally safe and sustainable. We urge the City to withdraw its objections to Ms. Anderson's approach to landscaping.

[signed by about 500 residents of West Lafayette and Lafayette]

Headlines accumulated, more than a few sympathetic—or at least concerned that their tax dollars not be spent on frivolous legal battles. For the mid-1995 court event, I aligned expert witnesses from Indiana (one on native plants, another on mosquitoes), from Ohio (about urban thickets), and from New York (that state's most eminent expert on rodents and bats). They all visited my home one weekend before the court date, which was basically a party as there were no mosquitoes and no rodents, but plenty of plants, scientists, and conversation. Media trucks—at least one from Indianapolis, and large enough to live in—began congesting the neighborhood.

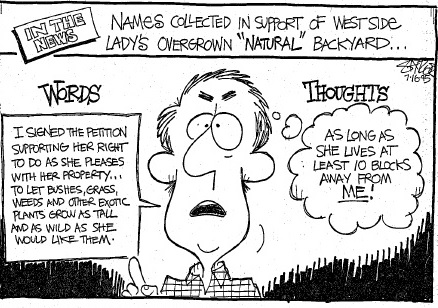

Profile and Cartoon from Indiana's Journal and Courier

The courtroom event was, once more, a challenge to my ethnographic prowess. Again, I would not budge on any matter forwarded by the city, and this time my attorney and his second-in-command held the line as well. As to the code violations, none could be substantiated. For instance, there had never been a lawn on this property since I purchased it, so demands that it be maintained were ludicrous. Accusations about the yard being "a fine mess" and a "public nuisance" were topped by it being called a "fire hazard", all undocumented.

To me, as an anthropologist, that assertion about my property being a fire hazard sounds close to wishful thinking, with more than a hint of witchcraft accusation. In evidence of my influence, a certain neighbor accused me of forcing him to exterminate 13 possums in a single evening, and another accused me of causing her cancer and its recurrence, although I guess not its interim remission. In 1996 a local conceptual artist depicted my yard in a gallery installation themed around "local notables". I wrote an accompaniment: "sight on site; sight on sight", underlining the fact that gaze is a voluntary act, rather different from most of the other senses.

By 1995 I was already deeply involved in searching out other cases of late 20th-century witchcraft accusation. Most cases around the U.S. involved women, anomalous in some way, often gardeners, and sometimes being attacked while they were perceived "down". I mentioned my father's 1988 death, but I could also have mentioned that of my stepmother in 1994, whom I had earlier brought to Indiana. Some of these women victims of neighborly hate had also just lost someone significant, one her own mother as a suicide in their joint home.

In this casual research over the decades I came to meet hundreds of people, at conferences besides the individuals in case studies. I gave numerous talks, but published little, given other tempting projects, and because I became overwhelmed by the escalating number of incidents surrounding urban land use. However, in the spirit of, "... make lemonade", I also embarked on documentary writing in genres where I had no expertise; think: courtroom drama, film, or why not a musical! In these unfinished and certainly unproducible drafts I cleverly chose pseudonyms for the major players, leaning on actors I could imagine playing them: Jim Carrey as the city attorney; Jerry Seinfeld and Johnny Depp as my erstwhile attorney-pair; Amy Poehler as my supportive student; and Cher for myself, even though I could also use "K(aye) Ossity" without fear of being sued.

Until 2012, the foregoing litigation was still on the books. I guess the City hoped to trip me up if I dropped my guard. I should mention that the assessed value of my property has increased while presumably that of my neighbors (including at least one colleague) has not suffered. The only thing I have done meanwhile, as sort of an insurance policy, has been to engage a delightful retired forester to visit my premises twice a year, who then writes a form letter to the judge, while bringing me native wild plants and maple syrup.

Dr. Myrdene Anderson is an associate professor of anthropology at Purdue University, where she continues to oversee a lawn in the midst of ecological succession. Dr. Anderson has engaged in ethnographic research in a variety of settings, ranging from community garden associations in the U.S.A. to the international and interdisciplinary movement of artificial life in biology, but she is best known for her fieldwork among Saami reindeer-breeders in Norwegian Lapland, which research commenced in 1971 and continues to date. Her recent reflections on dog herding and ethnography were published in Ethnobiology Letters and can be found here.

For more information on this story and on lawns and ethnobiology, please track down:

Journal and Courier, 25 May 1991

Windows With Curtains of Greenery Outside ... Myrdene Anderson's Battle With West Lafayette, Community Times 2.5, May 1995: 1, 6.

Fight to let yard grow wild continues; WL city officials want court-ordered lawn care, Journal and Courier, June 1995

Yard battle has gained little in West Lafayette (editorial), Journal and Courier, 16 July 1995: A10. WITH CARTOON (that says it all, NIMBY or how about NIYFY (not in your front yard)

Pollan, Michael. Why Mow?; The Case Against Lawns. New York Times Magazine, 1989 <link>

Robbins, Paul. Lawn People: Howe Grasses, Weeds, and Chemicals Make Us Who We Are. Temple University Press, 2007. <link to review>

Wasowski, Sally and Andy Wasowski. Requiem for a Lawnmower. Rowman and Littlefield, 2004. <link to publisher, Dr. Anderson is profiled in the book>

Comments (1)