Digging for traces of eastern Africa’s first farmers

Digging for traces of eastern Africa’s first farmers

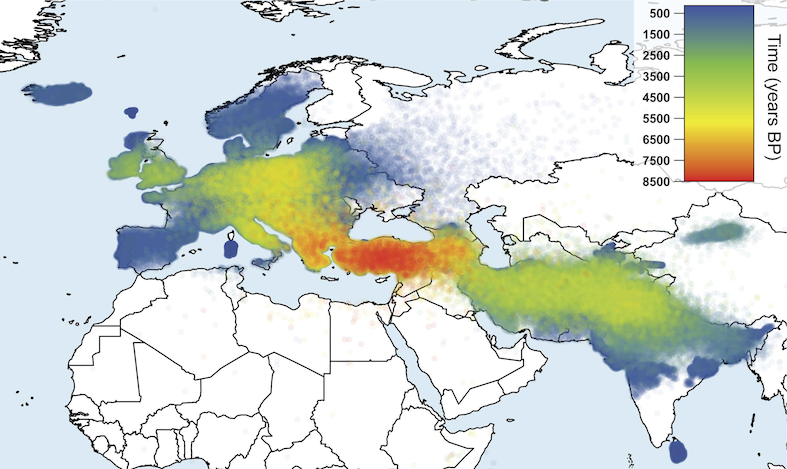

If you have ever taken even a passing interest in the origins of agriculture, you have probably heard of the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis. This is the theory that the world’s most widely-spoken language families are associated with the rapid expansion of farming societies into lands previously occupied by hunter-gatherers. Primarily associated with archaeologist Peter Bellwood, the Hypothesis was popularized by Jared Diamond in his best-seller Guns, Germs, and Steel, and is also a staple of most Introduction to Archaeology courses. One of the most famous examples is the Indo-European language family, which includes almost all modern European languages as well as many important Asian ones, like Persian, Hindi, and Bengali. If the Hypothesis is correct, this language family spread across Eurasia during the Neolithic Period, the era of first farmers. (Like most grand theories in archaeology, this one has been met with a flurry of case studies that contradict, complicate, or render more interesting the original narrative…)

The expansion of Indo-European Languages according to the “Anatolian hypothesis.” Photo: Wikimedia Commons, after Gray and Atkinson 2003.

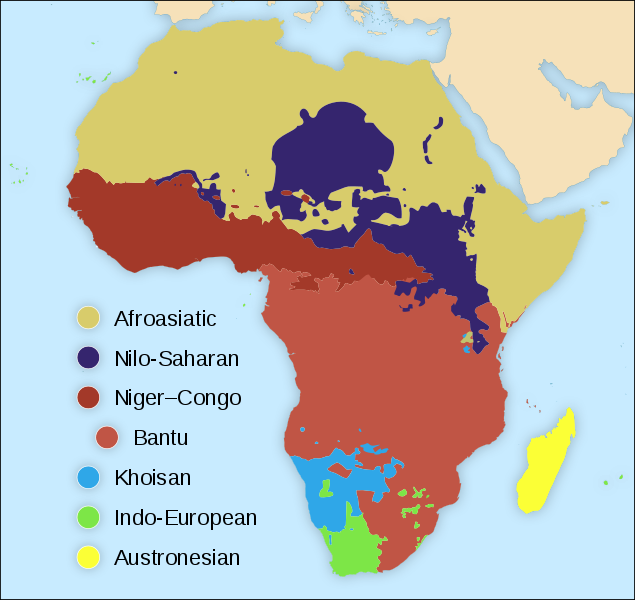

Only slightly less well-known is the Bantu Expansion, a proposed migration of agricultural people from their homeland in west-central Africa into eastern and southern Africa. Today, Bantu languages are widely spoken by agricultural communities across most of sub-Saharan Africa, and historical linguists and geneticists have argued that these languages and their speech community diverged relatively recently – beginning around 5,000 years ago. This aligns with the archaeological record, which shows a change in material culture in west-central Africa beginning at roughly the same time, then sweeping across eastern and southern Africa beginning around 2000 years ago. Did sub-Saharan Africa’s first farmers really expand across most of the continent in just a few hundred years, pushing aside or assimilating earlier communities?

Schematic map of Africa Language Families. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the fame of the Bantu Expansion as an example of the rapid spread of agricultural societies, there is a pretty major hole in the archaeological evidence for this scenario: the remains of the ancient crops themselves. The tiny remains of ancient plants are difficult to spot while excavating, and they are very fragile. This combination of unfortunate attributes meant that for the first century or so of scientific archaeology, plant remains were only recovered from very special and rare contexts, like caves or burials, where perfect preservation made them hard to miss. Beginning in the 1960s, archaeologists started using a method called flotation to recover the remains of plants from ordinary, run-of-the-mill sites.

Flotation: 1. Put sediment in a bucket of water, let settle. 2. Pour orangics over fine mesh. 3. Dry!

The idea is simple: organic components of sediments are usually less dense than water, while the inorganic components (the vast majority of what you might think of as dirt) are usually denser than water. This means that if you empty a bucket of sediment into a bucket of water, the organic material will conveniently float to the top. You can then pour it off, dry it out, and examine it (with the help of a microscope). The problem is that, until very recently, flotation had been carried out at very few sites associated with the Bantu Expansion, so there is little direct evidence for early crops from these sites. Call me biased (I have a PhD in ancient plant remains from archaeological sites), but I don’t think we can truly get to know these early farmers without studying their crops. After all, the fundamental agricultural input is the seed (or root, or fruit, in the case of many African crops, but that’s a story for another day).

In recent years, paleoethnobotanists have been hard at work conducting flotation and other kinds of botanical sampling at sites across eastern and southern Africa, and their efforts are starting to yield a more nuanced picture of early agriculture in these regions. Last year, the results of investigations at 15 sites spanning the transition from foraging to farming in coastal Kenya and Tanzania were reported in Quaternary International. These researchers argue that adoption of agriculture in this region is better characterized as a mosaic than a migration, with communities adopting crops at different rates or continuing to rely on wild resources for hundreds of years after the supposed Bantu Expansion. However, this is in contrast to investigations in Rwanda documenting assemblages dominated by domesticated grains and legumes dating to c. 400-1100 AD and associated with the classic trappings of Bantu Expansion material culture. Of course, there is no reason to assume that two such different regions would follow the same trajectory – but the contrast only highlights the need for more regional studies. There are still many gaps in the record, one of which lies in the highlands of western Kenya.

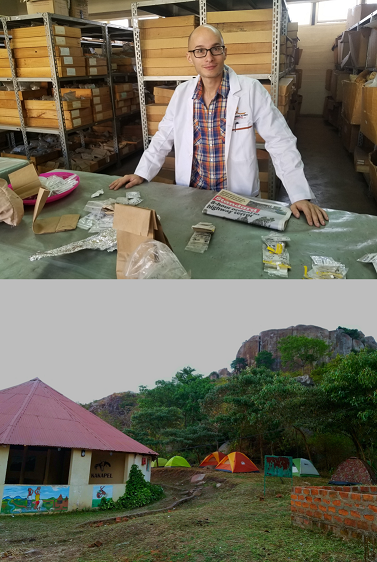

Kakapel Rockshelter, Western Kenya. Photo: N.G. Mueller

It was with this in mind that the National Museums of Kenya and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History invited me to join their search for evidence of the first farmers in eastern Africa. Project director Steven Goldstein started his career studying the expansion of pastoralists into eastern Africa, but recently has been investigating early agricultural sites in Zambia and now Kenya. At the beginning of February, we set out from Nairobi with an interdisciplinary team of archaeologists to conduct excavations at Kakapel rockshelter. Kakapel is located in the highlands near Lake Victoria, on the border between Kenya and Uganda.

Top: Project director Steve Goldstein, working in the National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi. Bottom: Our camp below Kakapel rockshelter.Photos: N.G. Mueller.

Today, it lies in the midst of rich agricultural lands, right on the hypothetical route taken by Bantu peoples on their trek into eastern Africa. Previous excavations there had recovered Urewe-style pottery, the calling card of the Bantu Expansion in the Great Lakes region of eastern Africa. Abundant charcoal and grindstones were also found in the deep deposits under panels of rock art depicting domesticated animals (pictured above). All of these factors recommended Kakapel as an ideal location to recover early evidence for farming.

Team members working in deep deposits in Kakapel rockshelter.Photo: N.G. Mueller

I had an additional interest in this region, grounded in my study of plant domestication. For most of our important crops, archaeologists have reconstructed roughly where and when they were first cultivated. We have tracked the process of domestication by recovering sequences of archaeological crop remains from the region where each species was first cultivated: first, the harvesting of wild plants, then slow transformation as populations of cultivated plants evolve under human care, and finally a recognizably different domesticated variety. Of the world’s major grain crops, one of the last big mysteries is finger millet (Eleusine coracana). Producing an abundance of adorable (and highly nutritious) little seeds, finger millet is an important crop in sub-Saharan Africa and on the Indian subcontinent, where millions of farmers value it for its hardiness at altitude and drought tolerance.

Finger millet. Photo: Wikimedia commons.

Although botanists have long believed that finger millet was domesticated somewhere in the highlands stretching from Ethiopia to Uganda based on the diversity of modern crop varieties in that region and the distribution of its wild ancestor, there is almost no supporting evidence from the archaeological record. A single grain from pre-Aksumite (c.50 BC- AD 150) Ethiopia is the earliest evidence from the region, but finger millet then disappears from the record for several hundred years, popping up again around 700 AD in Ethiopia, along the coast in Kenya and Tanzania, and in Rwanda. Meanwhile, finger millet had somehow made the long journey across the ocean to India, where it has been recovered in contexts possibly as old as late 2nd millennium BC. In other words, the earliest archaeological finger millet comes from thousands of miles away – and across the Indian Ocean – from where it was first cultivated. This kind of situation screams MISSING DATA, and I am a sucker for an archaeobotanical mystery. Kakapel lies squarely in the region where finger millet domestication likely occurred. I was hoping to get lucky and recover some badly needed evidence for its early cultivation there.

Eleusine coracana grains from the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium at Cornell University. Photo: N.G. Mueller

We spent three weeks excavating at Kakapel, recovering thousands of artifacts of daily life at this site during the first millennium AD. Some of the artifacts we found were familiar – they mirrored the agricultural landscape as it still exists today. Some of our neighbors slept in round houses made of wood and daub, simple structures that stay cool during the day and warm and night. We found remains of an ancient house constructed using the same methods.

Top left: A peice of an Iron Age house from the excavation, and houses constructed in the same way in our camp and on the neighbor's farm. Photos: N.G. Mueller

The neighbors’ cows, sheep, and goats visited our excavations daily – while cow, sheep, and goat bones were also among the most abundant artifact types. We also found artifacts that complicate the neat narrative of agricultural expansion – such as ceramics associated with the hunter-fisher-gatherer Kansyore sites on nearby Lake Victoria, and the remains of wild plants and animals. It will take some time (and radiocarbon dates!) to work out exactly what was happening at Kakapel, but we look forward to adding some locally situated detail to the story of early agriculture in this region.

Neighbors' cows were regulars on-site, and an almost entire nut, one of many to-be-identified plant species recovered from Kakapel. Photos: N.G. Mueller

For me, the most exciting finds were burn features – contexts likely to be full of charred plant material, such as hearths. We also found fragments of an ancient floor with plenty of charcoal stomped into it by daily traffic centuries ago. We collected about 350 liters of sediment from such features for flotation.

Steven Goldstein and Nick Blegan excavating an ancient floor (cross-section with lots of charcoal inclusions bottom right), and a peice of Kansyore pottery, probably from a group thought to be fisher-hunter-gatherers. Photos: N.G.Mueller and S.T. Goldstein.

By the end of the dig, I was spending half of each day floating these samples. Floating really required an effort on the part of the entire crew, since we didn’t have water at our camp and had to truck in jerry cans for drinking, bathing, and floating from a well 15 minutes down the road. Flotation takes a lot of water (about 20 liters per 10 liter sample, even if you’re being frugal), and it can be frustrating to use all that water and spend all that time fetching it without immediately being able to see the fruits of your labor.

Team bioarchaeologist Elizabeth Sawchuk and NMK intern Nick Nyeanteach excavating, me taking a flot samples, Fatima womaning the flotation station at camp. Photos: N.G. Mueller

But even to the naked eye, it was apparent that we were recovering A LOT of ancient plant remains, and when I got the chance to set up my portable digital microscope, we could also see that there was a huge diversity in well-preserved seed types in our samples – pure gold for a paleoethnobotanist! Having the microscope in the field also allowed us to quickly identify contexts that were yielding crop remains, and target those for sampling.

Doing some preliminary analysis in the field. We were lucky to have electricity to run the digital scope (most of the time!) Photo: E. A. Sawchuck.

I just returned to Cornell with the Kakapel samples, and the process of sorting and identifying all of the plant remains has just begun. While it is great to recover direct evidence for early agriculture, I was also excited to see so much variety in the samples. In a place as botanically diverse as Western Kenya, it will be challenging to identify all these seeds but I think it is well worth the effort. Archaeologists tend to focus on major crops once they arrive on the scene, but most agricultural people throughout history have relied on diverse crop systems and continued to manage important wild plants. I look forward to watching the image of one such diverse agroecosystem emerge from these samples in the coming weeks. Stay tuned!

By: Forage! co-editor Natalie G. Mueller

Comments (3)