A curious quest to rediscover lost crops

A curious quest to rediscover lost crops

An a hot August day in 2014, I found myself armpit deep in weeds and grasses on a creek bank in central Arkansas, following my friend Liz Horton as she swept the ground in front of us with a stick to scare off snakes. Kelsey Nordine brought up the rear, mastering her life-long ophidiophobia by dint of dedication to our common goal: to rediscover a lost crop. I remember this day as the spiritual beginning of my lost crops research, a journey of discovery that would transform me into the world expert on one unobtrusive little plant, erect knotweed. While it is easy to overlook this plant today, the archaeological record shows that it was an important seed crop for centuries in many Indigenous communities in eastern North America.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The following is reposted from my personal blog at ngmueller.net. If you want to find out more about the search for lost crops, I will be posting there regularly for the next six weeks or so as I travel the Midwest in search of elusive weeds with fascinating histories]

That day, I had the help of some formidable companions. Liz is the station archaeologist for Toltec Mounds, a site that was an important ceremonial and political center in the Late Woodland and Mississippian Southeast (from around 650 – 1100 AD). Back then, Liz was getting started building the Plum Bayou Garden at Toltec Mounds, a teaching garden that contains many of the plants used by Woodland communities in Arkansas (if you're in the area, you really should stop by -- it is an extraordinary place). She is also an expert in ancient fiber technology – baskets and clothing – and the plants that were used to create them. The daughter of two master naturalists and a native of the Ozarks region, she was the ideal guide to help me find an elusive and diminutive weed among the almost scary plant fecundity of August in Arkansas. Like me at the time, Kelsey is a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis specializing in pre-Columbian agriculture. She was working in the Maya world, but her growing interest in the plants and people of eastern North America was evident from her willingness to keep me company on this wild weed chase. We did not find any erect knotweed that day, but later on Kelsey and I did find thousands of seed ticks on our ankles in the seeming luxury of our air conditioned Motel 6 room.

Erect knotweed -- if you can spot it! I found this one with the help of Missouri Botanical Garden botanist Alan Brant. I ended up writing a whole dissertation about this plant -- read all about it here.

Maybe it seems strange that I remember that day, when I failed to find a lost crop, as the beginning of the journey. But scraping ticks off your legs with a credit card in a motel bathtub and not finding what you’re looking for – then laughing about it in bed with a tall boy of PBR – is part of the distinctive flavor of my field work. It’s not the only flavor though – there’s also the taste of frozen pickle pops after long hot car rides with the windows down, the indescribable beauty of a native prairie remnant blooming in May, and the excitement of finding whole populations of endangered plants somehow thriving in tucked away corners of the industrial agricultural landscape.

Clockwise from top: Survey for Lost Crops veteran Maggie Spivey-Faulkner, enjoying a roadside Pickle-Ice; Cherokee Prairie echinacea in bloom, an enormous population of maygrass hidden among the cornfields of southeastern Arkansas; Maggie, Liz, and my mentor Gayle Fritz at the Plum Bayou Garden; me the day I found my first stand of erect knotweed.

Now, as I get ready to set out once again with my plant press and my measuring tape, I’ve decided to start writing about these experiences. The Survey for Lost Crops, as I’ve come to call this endeavor, is an esoteric quest to find the remnants of an ancient agricultural system, but along the way it also brings me to parts of the 21st century rural landscape that are seldom seen. It also brings me into contact with people who are protecting the land, its native flora and fauna, and its deep history in unique and unexpected ways amid what appears from the highway to be a desolation of genetically modified corn and soybeans.

Paul Krautman on his farm talking lost crops with my partner, Don Conner, another Survey stalwart. Paul's alternative farming methods, especially his limited use of herbicides, make room for native plants like erect knotweed (foreground) to persist in agricultural landscapes.

So what are these lost crops I speak of? Here they are!

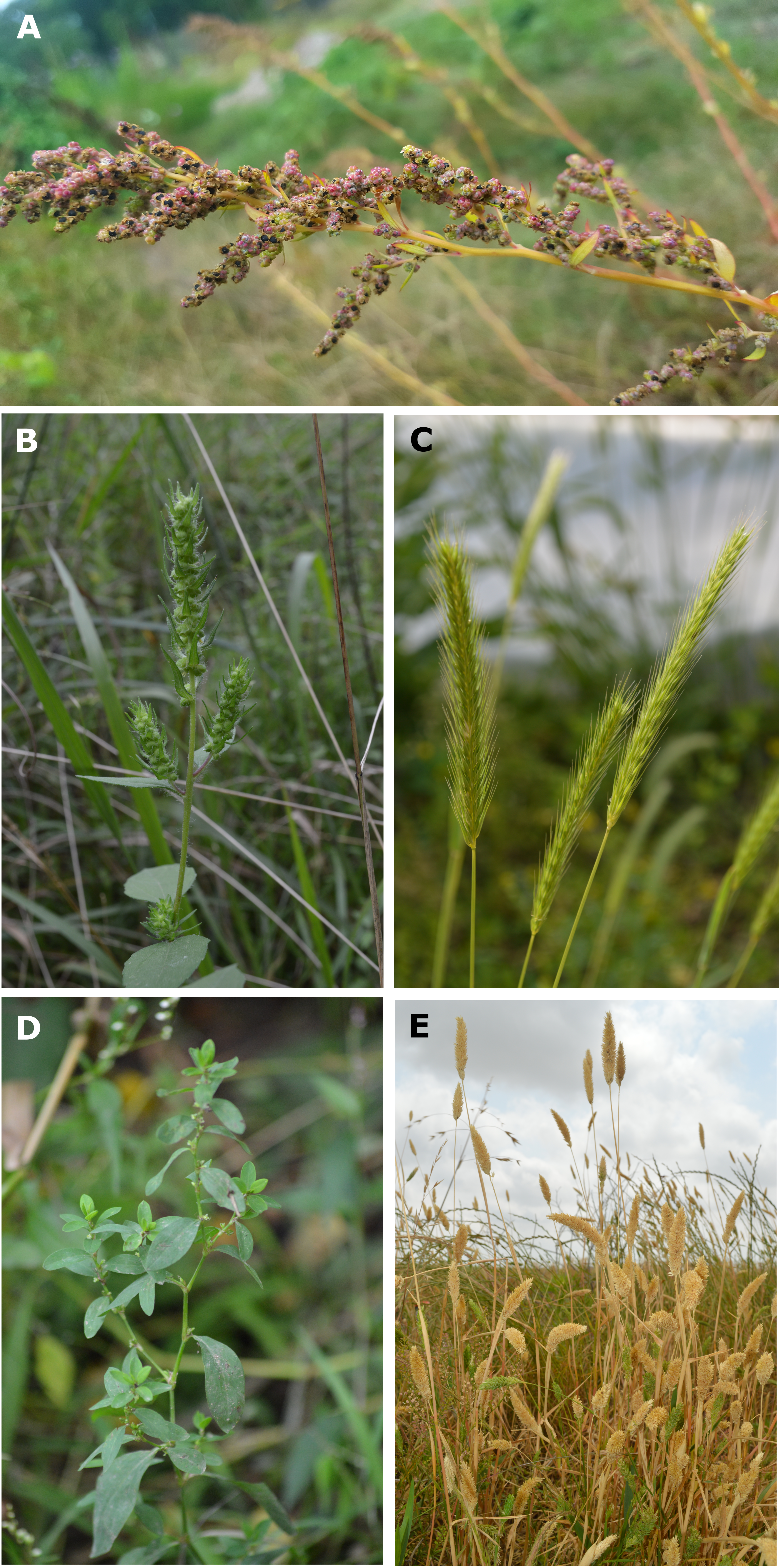

From Mueller et al. 2017. a) goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri); b) sumpweed/marshelder (Iva annua); c) little barley (Hordeum pusillum); d) erect knotweed (Polygonum erectum); e) maygrass (Phalaris caroliniana)

Don’t feel bad if you don’t recognize them. When you think of Indigenous North American cuisine and agriculture, you probably imagine three crops that are very far from lost: beans, squash, and of course, maize (most people call it corn, but that’s actually an old European term meaning any kind of grain – the name shows how important it became to European colonists, huh?).

The kind of maize agriculture practiced today by this farmer (and good sport) in Illinois would have surprised the ancient farmers who developed this crop. They grew diverse maize landraces in a complex polycrop system with many other plants. Photo credit: Andrew Flachs.

These three crops were indeed the staples in a complex domesticated landscape that supported Indigenous people at the time when their land was invaded by European colonists. Maize, beans, and many common varieties of squash originated in Mexico, where their wild ancestors were first domesticated, and they reached eastern North America through trade. But that doesn’t mean that expert farmers in eastern North America played no role in creating the crops we know today. For the entire history of agriculture up until the early 20th century, farmers were responsible for selecting and saving their own seed from their own crop, or else trading for seed with neighbors. What archaeologists call the “tropical crops,” those that originated in Mexico, had to be adapted to the temperate climate of eastern North America, a process that likely took centuries of careful observation and experimentation.

I photographed these teosinte (the wild ancestor of maize) and maize sprouts at a workshop on seed saving at Native Seeds Search in Tuscon, AZ (as part of the 2016 Ethnobiology meetings!). This seed bank houses hundreds of landraces of crop plants, including this sprouting maize variety, that are specially adapted to the Sonoran Desert. The same crop diversity was also characteristic of ancient crops in the East, and many Indigenous communities still maintain their traditional landraces of maize and other crops.

We know from the archaeological record that maize, beans, and Mexican varieties of squash (such as pumpkins) were not widely grown in eastern North American until the last few centuries before the arrival of Europeans – beginning around 900 AD. But agriculture began in this region thousands of years earlier. Which brings me back to the lost crops – if they were lost, how do we know about them? That story begins in the 1960s, when archaeologists began to use a new technique called flotation to recover plant remains from archaeological sites. It’s not rocket science – you take a soil sample from an archaeological context, like a pile of ancient garbage or a storage pit, and you put it in a bucket of water. The organic material floats to the top, you skim it off, dry it out, and look at it under a microscope.

My students processing flotation samples near Avon, NY, in the summer of 2011, and the end results we hope to find: tiny fragments of ancient plants (in this case, erect knotweed sprouts!)

This simple methodological innovation changed everything, though. As thousands of liters of sediment were floated all across eastern North America, it became apparent that several unknown crops had been cultivated for their seed, while at the same time the advent of radiocarbon dating revealed that agriculture dated back a whopping 4,000 years – much longer than anyone had thought before. To answer early skeptics, paleoethnobotanists got creative. They dissected ancient human poops – yes! Poops! – and found that they were full of the seeds of the lost crops. They also found the lost crops stored in baskets and bags or bundled in dry rock shelters. By carefully analyzing the size and shape of the ancient seeds, they were able to demonstrate that some of the lost crops were actually domesticated. This means that they had diverged, in the evolutionary sense, from wild populations and could be recognized as distinct sub-species.

Left: Excavating a pit full of erect knotweed seeds (Photo courtesy of Neal Lopinot); Right top: ancient human poop from Kentucky; Right bottom: ancient bundles of maygrass from Arkansas.

The study of the lost crops is only two academic generations deep. My dissertation adviser, Gayle Fritz of Washington University, was one of the scholars who showed that the lost crops were domesticated. Her adviser, Richard Yarnell, did some of the pioneering studies of the lost crops, including the first analyses of ancient poops. Because we’ve only known about these crops for a few decades, there are a still a lot of unanswered questions. For me and my colleagues, many of these questions can only be answered by interacting with the living plants.

Growing Lost Crops Symposium participants, Athens, GA 2016. Left to right: Me, Gail Wagner, Paul Patton, Liz Horton, Daniel Williams, Gayle Fritz, and Logan Kistler (and some lost crops, of course!)

Here we all are luxuriating in our shared nerdiness at the Growing Lost Crops symposium, the first of its kind, last fall at the Southeastern Archaeological Conference meetings. If you want to read more about this research, check out the paper we recently published on some of the preliminary results of our projects. I am setting out on round three of the Survey for Lost Crops tomorrow, and I look forward to sharing stories and findings along the way this time!

By Natalie G. Mueller, Forage! co-editor

Comments (1)