Creating herbaria with tribes in the Klamath River Basin

Creating herbaria with tribes in the Klamath River Basin

By Megan Mucioki, Ph.D.

Herbaria, collections of pressed, dried, and preserved plants including non-vascular specimens and field notes, are valuable research and educational tools housed in universities, museums, or botanical gardens. Well preserved specimens can last 200 years or more and are increasingly used by researchers to understand the effects of climate change on plant development and distribution, explain plant relationships, and map historical and contemporary native and invasive plant distributions (just to name a few uses). Usually large herbarium collections span continents, rarely with a solely local or regional focus and rarely housed and administered by Indigenous people. In 2016, as part of a collaborative Tribal Food Security Project between researchers at the University of California at Berkeley and tribes in the Klamath River Basin, two tribal herbaria were founded by the Karuk and Yurok Tribes (Photo 1). With the intent to support tribal sovereignty over cultural resources and related data, the collections are housed at a tribal department and governed by each respective tribe. The collections primarily focus on cultural food, fiber, and medicinal plants found throughout the Karuk and Yurok Tribes’ respective ancestral territory and used by these tribes since time immemorial. The Karuk and Yurok herbaria are two of three herbaria in the nation led by Native American tribe or nation, the other being the Navajo Nation Herbaria.

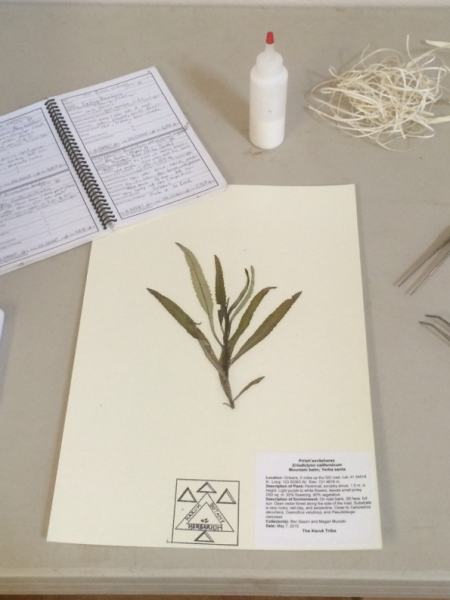

A mounted specimen ready for filing in the Karuk Herbarium. Folks from the Karuk Department of Natural Resources worked together with myself to collect voucher specimens of culturally important plants and press, dry, mount, and prepare the specimens for long-term preservation.

While the ex-situ aggregation of cultural plants may seem inherently contradictory to tribal values and goals to keep cultural plants living as part of their culture, ceremonies, and diets, the collections we established have evolved to complement the goals of tribal cultural plant revitalization or restoration by providing an educational and research tool for the tribes to use with youth and adults or to integrate into various natural resource focused projects. Ultimately, the value and power of tribes having a sustained library of cultural plants found within their territory that can span centuries is of unfathomable valuable to support land management decisions, the need for tribal management of ancestral lands, explain impacts on climate change on cultural resources, tribal sovereignty over land and cultural resources, and much more.

The grand opening of the Karuk Herbarium at the Karuk People’s Center in Happy Camp, CA

Integrating ways of knowing

Myself and mentors, Tom Carlson and Jennifer Sowerwine at UC Berkeley in partnership with the UC-Jepson Herbaria, worked closely with collaborators from the Karuk and Yurok Tribes to discuss the values and procedures used in herbaria governed solely by western scientists and values and systems rooted in Indigenous ways of knowing that should integrated into the herbaria. In the field, I teamed up with natural resource technicians from each tribe to collect primarily flowering and fruiting culturally important plants during the spring, summer, and fall months (Photo 3). Through our field trips, natural resource technicians were trained in methods of voucher specimen collection, pressing, and mounting. Tribal codes and values of sustainable harvesting from plant populations, only collecting from populations which could sustain the disturbance and only taking enough needed for the voucher specimens, are used. In the field, tribal natural resource technicians guide the geography of our specimen collection and coordinates are taken at the discretion of tribal collaborators. Additionally, ethnobotanical information is integrated into the aggregated data for each specimen and mounted specimens are organized by Yurok or Karuk plant names rather than by plant family or genus.

Ben entering data into Simpson’s yellow book to accompany an array of specimens ready to be pressed. For each species collected, we document data on the plant habit, environment, associate species, and geographic location.

Workshops and skill building

Throughout the five-year Tribal Food Security Project and beyond, workshops on collecting and mounting specimens were held with tribal youth and adults (Photo 4). Attendees learned how to collect and press voucher specimens to contribute to their tribe’s herbarium. Anyone in the community can contribute to the herbaria and plant presses are available for borrowing at the Karuk Department of Natural Resources. Hands-on activities on plant pressing and mounting are also carried out with youth at local schools and tribal summer programs as well as integrated into the K-12 tribal curriculum developed by Lisa Hillman, Program Manager of the Karuk Tribe's Píkyav Field Institute.

Karuk youth learning about cultural plants and pressing and mountingspecimens for the Karuk Herbarium.

Recently the UC-Karuk collaborative was awarded a three-year grant by the USDA focused on forest agroecosystem resilience in changing climates and assessment of cultural food plants. We continue to expand the collections and our skills through our new project. In March UC Berkeley researchers and Karuk natural resource technicians gathered for a workshop in Berkeley focused on collecting and preserving bryophytes, fungi, lichens, and algae. New skills acquired at this workshop will be applied to expand and diversify the Karuk collection, adding 100 new specimens in the next year and many more in years to come.

Attendees and instructors at the workshop for advanced skills in collecting and mounting voucher specimens at UC-Jepson Herbaria in March.

Making spore prints of fungi specimens.

Learning wet mounting of algae or seaweed which turn out to be beautiful art-like specimens when finished.

Megan Mucioki is a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at the University of California at Berkeley. Megan’s research engages Indigenous and rural communities in food and seed focused research that informs the in-situ conservation of traditional food plants and explores relationships between access to traditional foods and household seed and food security. For more information on the collaborative research and extension projects Megan is a part of visit: https://nature.berkeley.edu/karuk-collaborative/