Cotton Complexities in South India

Cotton Complexities in South India

By Andrew Flachs, Assistant Professor of Anthropology (Purdue University)

As more than 1 billion people around the world gather to celebrate Diwali, cotton is nearly ready to pick in Telangana, India. A few years ago, Telangana cotton farmer Shiva and I travelled to the city to buy name-brand cottonseeds from a shop with a reputation for selling high-quality agricultural inputs like seeds and pesticides. The seeds Shiva sowed in June brought forth a terrific harvest that year, withstanding pest attacks, and redoubling investments in pesticide sprays, fertilizers, labor, and plowing. Ripe bolls, having withstood the vagaries of an increasingly unpredictable monsoon and new insect pest cycles, bring the promise of fireworks, new clothes, presents, and parties when sold in time for the late autumn festivities. Farmers like Shiva can breathe sighs of relief, content that, this year, their gambles have paid off.

Shops in Warangal, India. All Photos by Andrew Flachs.

Farmwork does not always proceed so smoothly. That same year, Shiva’s neighbor Dharwesh found his cotton stems and the undersides of his leaves covered in whiteflies, immune to Bt Cotton’s genetically modified pesticidal genes. Panicking, Dharwesh borrowed a motorized pesticide sprayer to treat his fields. A few rows into his field, Dharwesh’s machine overloaded, engulfing him in a cloud of smoke and insecticide. He collapsed, awakened minutes later by a neighbor who rushed him to a nearby clinic. Dharwesh recovered, but some of the insecticide was lodged in his left eye for too long. He is now blind in that eye, a fate better, he explains, than it might have been.

A farmer sprays genetically modified Bt cotton for non-target pests.

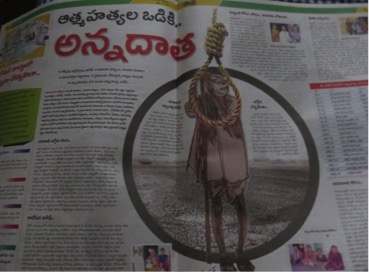

Their neighbor, Bhadra, across the road was even less lucky. A cotton farmer who has had several unlucky seasons, lost money to laborers, and borrowed to afford agricultural inputs like fertilizers and pesticides grows increasingly anxious. A young man, Bhadra’s marriage prospects, and thus his standing among his peers and his place in the village, were in jeopardy with every insect attack and lost rupee. He heard a rumor that the woman to whom he was arranged to be married was now pursuing other husbands. Overwhelmed, he drank several gulps of the concentrated insecticide that is present in every Telangana cotton farmer’s home. Bhadra vomited twice, and died later that day, joining 11,771 farmers who committed suicide in that year.

Telangana newspapers run stories lamenting farmer suicides weekly during the summer season.

200 kilometers southwest, Mahesh does not decide between different cottonseed brands at a shop. Because his village has decided to sell organic cotton, he is legally prohibited from planting genetically modified (GM) seeds. Instead, he receives them at a discount from an NGO that helps the farmers in his village comply with organic standards and then sells their cotton to interested buyers in Europe, Japan, and North America. Mahesh has reaped lower overall yields than the farmers around him, but he has found greater stability in this uncertain market and a new celebrity as a leader in a village that is bucking the trend of an agrarian crisis defined by suicide, stagnant yields, and pesticide overuse.

Farmers, lucky and unlucky, bring this cotton to shelves around the world. Much of my research since 2012 has asked how GM seeds and organic certification might help resource-poor farmers. As an ethnobiologist, I am interested in these technologies not as new fixes dropped into a social vacuum, but as elements of a larger set of relationships between people and plants. To answer this question, I began by looking at seeds because a seed is a choice that cannot be taken back. As seeds grow, farmers care for them, continuing to make choices that they hope will lead to yields, profits, and a good life. In Telangana, India, the seemingly simple decision about which seed to plant has taken center stage in a larger debate over two mutually exclusive visions for the future of agriculture: genetically modified organisms and certified organic farming.

A cotton worker and her son rest in between packing cotton into a gin on the outskirts of Warangal, Telangana.

The future of agriculture, because the stakes are high and the implications far reaching, has drawn particular scrutiny in India. India has nearly 600 million small farmers, and the cotton sector has been particularly hard hit by issues of production and pesticide overuse. In the mid 1990s, cotton pesticide sprays accounted for nearly half of all pesticides used, even though it was planted on just five percent of the arable land. Some blame GM seeds or insects for this agrarian distress and others celebrate new technologies and programs as means to empower rural economies. These are important perspectives, but I think that this technological focus draws attention away from the daily, social ways that people make decisions. Instead, through first-hand case studies with farmers, rural professionals, NGOs, government officials, and plant scientists working on GM cotton and certified organic supply chains, I’d argue that the biggest impact of these technologies is in the ways that they transform farmer knowledge and thus reshape agrarian life.

Commercially introduced in 2002 with three options, farmers now choose between 1,500 different seeds. Each one is a potential windfall in a context where agriculture is always a gamble. In the GM cotton sector, farmers leverage ambiguous input and labor costs against uncertain benefits of profit, often mimicking the decisions of their neighbors or seeking the advice of seed dealers before planting. This is a vision of agriculture that lives or dies by good yields from a cash crop. The problem is that in this speculative environment, wanting good yields can be very far from taking steps to get them. Through a wide range of data collected since 2012, I’ve seen that farmers don’t see clear yield differentials that would help them choose particular seeds, farmers gamble by switching seeds frequently, farmers themselves don't know very much about the seeds they are planting, and the market is increasingly confusing. Seed choice is paradoxically crucial yet uncertain, made amidst a deluge of marketing, competition, consumption, and the persistent erosion of experiential knowledge. This new normal of the farm masks a deep ambivalence about what it means to farm and to live well in rural India. Today, more than 95% of all farmers sowing cotton use GM seeds. This system is very effective at selling seeds and associated inputs. And yet, because it erodes farmer knowledge in favor of commercial expertise, it fails to address the underlying instabilities in rural India that are driving rural distress.

Seed, pesticide, and fertilizer shop in Warangal, Telangana.

Much like GM technology, organic agriculture may help some farmers, under certain conditions, through alternative marketing. However, this story is complicated. Organic agriculture is not a panacea and it rarely works according to the same agricultural logic of investments and yields that many farmers are used to following. Most organic cotton farmers in practice reap far lower yields than their GM-growing neighbors, and so organic certification programs incentivize low yields and strict regulatory protocols with material rewards like seeds, jobs, and financing, as well as new forms of celebrity and media attention. Still, I think that it is a mistake to say that these spaces are performative and thus illegitimate. Quite the opposite: the ways that organic programs underwrite vulnerability, create social capital, and create new reward structures for farmer success determine their lasting success. That is, farmers experience the promise of organic cotton agriculture as a strategic choice to follow didactic instructions and a performance on a new kind of agricultural stage, and my data show that these projects tend to succeed or fail on those terms. Leaning into this production can build not just stability, but reinforce greater on-farm biodiversity.

An organic farmer waits for a cameraman to get in position before spraying a homemade, plant-based pesticide.

Ethnobiologists who study complex systems like agriculture often reach these kind of muddied results – it’s complicated, we explain with exasperation to people who want the short version. And yet I do see signs of hope in the data. Ultimately, the key underlying issue cotton farmers face is the unstable nature of seed choice, investments, and returns. Seeds, GM or not, sold and managed in a more collective system help to alleviate the symptoms of South India’s agrarian distress. By filtering the seed market, storing cotton, securing financing, and connecting farmers with buyers, cooperatives across South India help farmers learn about their seeds and apply local management knowledge. Through collaborative meetings and grassroots consultations to troubleshoot the local complications of farmwork, cooperatives are restoring trust and iterative learning to a labor sector in dire need of stability. Cooperatives in both settings are taking the time to work with farmers and incentivize a different set of ways to be successful in an agricultural sector where cotton farmers internalize their failures and commit suicide. In doing so, they address fundamental causes of agrarian distress where GM seeds or mandatory organic regulations only scratch the surface.

Farmers working with a cooperative show off diversified saved seeds including pulses, millets, and maize.

There is a persistent danger in seeking technological fixes for problems rooted in complex agricultural, political, social, and historical issues. In part, this is because the practice of sustainable agriculture on the farm, let alone the global challenge of feeding or clothing the world, is a social, and not technological, question. Ultimately, the allure and danger of technological fixes is that they ignore the daily, messy, important, social work of agriculture. People wishing to wear clothing have an imperfect choice in an imperfect market. As consumers we can, in some ways, vote with our dollars to support social institutions that benefit farmers. This requires us to be an informed populous capable of exercising these choices, and we do not always have such information available in the moments when we buy cotton. And yet, sometimes and if we can, our choices do have measurable impacts on others – not because our consumption or lack thereof will lead to transformative change, but because we support larger institutions that incentivize local knowledge, management, and technology that allows rural communities to live well, on their own terms, as farmers. And if you like that, boy have I got a book for you.

https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/cultivating-knowledge

Andrew Flachs is an assistant professor of anthropology at Purdue University specializing in food and agriculture. His book, Cultivating Knowledge: Biotechnology, Sustainability, and the Human Cost of Cotton Capitalism in India, was released in November 2019 with the University of Arizona Press.

Comments (1)