Burning cathedrals: Thoughts on Notre Dame, Chaco Canyon, and the slow moving fires consuming sacred places

Burning cathedrals: Thoughts on Notre Dame, Chaco Canyon, and the slow moving fires consuming sacred places

By Natalie G. Mueller, Forage co-editor.

When I saw the first pictures of the Cathedral of Notre Dame burning, I thought, “I’m sure they are getting it under control. They won’t let it burn.” At that point there was only smoke billowing out around the spire. A couple hours later I watched in horror as the spire collapsed onto the blazing roof, which was now transparent and glowing from within. I was glued to the news all day. By the time Notre Dame spokesman Andre Finot was repeatedly misquoted as saying “Everything is burning, nothing will remain…” (he went on to say, “of the frame”), I was sitting at my desk sobbing.

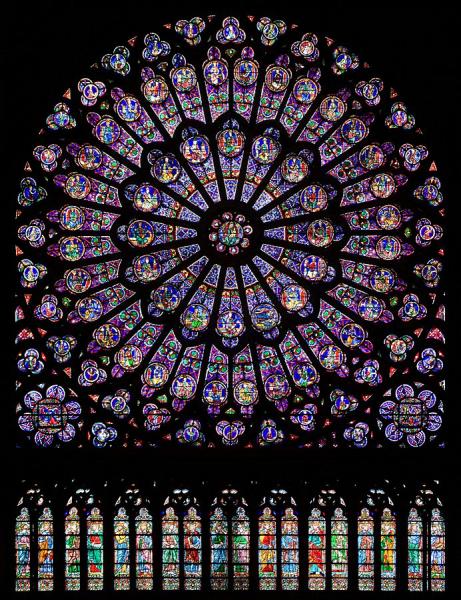

I was afraid that the combination of heat and water would damage the masonry so much that I would wake up to find the cathedral a pile of rubble. I was sure that the rose windows, 13th century masterpieces of color and light that had filled me with joy and awe, were gone. But I woke up to find that the worst had been prevented: Notre Dame is still standing and many of her treasures have been saved, including those beloved, irreplaceable windows.

The north rose window of Notre Dame. Wikimedia commons.

Now that I’ve calmed down a little, I’ve started to think about my reaction to this fire. I am always sad and angry when places that are full of history and beauty are destroyed, but I’ve never spent a day intensely grieving for a building before. As an anthropologist, I have an intellectual understanding of the fact that places can hold the identity and history of people, both of individuals and of communities. Now I fully realize how lucky I am that, until yesterday, a place that holds a part of me has never been under serious threat. In his ethnography Wisdom Sits in Places, Keith Basso writes that for his Western Apache collaborators, the landscape is “a repository of distilled wisdom, a stern but benevolent keeper of tradition, an ever vigilant ally in the efforts of individuals and whole communities to maintain a set of standards for social living that is uniquely and distinctly their own.” Children are told, “Drink from places, then you can work on your mind.”

Notre Dame at sunset. Nicolas Windspeare via Flickr.

Paris was only my home for a few months, but I drank as deeply and as often as I could from Notre Dame. The first time I saw it was at sunset in the summer of 2004, about an hour after arriving in Paris for the first time. There was a concert being held, and music spilled out of the giant open doors into the ever-crowded parvis. Inside, I was struck by the same visual metaphor that inspired Antoni Gaudí to create his seemingly organic cathedral, La Sagrada Familia, 500 years after Notre Dame was completed: great gothic cathedrals are like towering forests made of stone.

Vault of Notre Dame. Wikimedia commons.

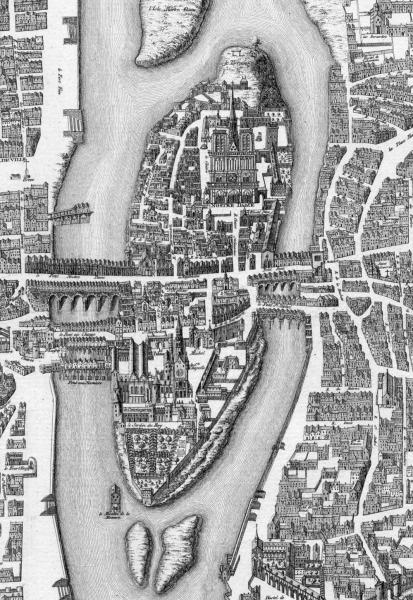

Walking down the apse of Notre Dame is like walking up an aisle of trees whose branches meet overhead, and coming into the crossing is like entering a clearing full of sunlight. It was the impact of that place more than anything else that made me resolve to come and live in Paris, which I did 3 years later. During the months I lived in that ancient city, I visited Notre Dame at least once a week. To me it was a symbol of the greatness of the human spirit, and the capacity of human minds to imagine magnificent creations and bring them into reality. I learned that the site of Notre Dame was held sacred by the Parisii, Paris’ Iron Age Celtic inhabitants. The Romans co-opted the power of the place by building a temple to Jupiter. That temple was replaced by a continuous succession of Christian churches, culminating in the great cathedral, which was completed in the 14th century. This was the first place that I had visited that seemed saturated with veneration. Centuries of sacredness create a palpable energy in the air around Notre Dame, and it is clear from the global spasm of grief that occurred yesterday that I am not the only one who has felt it.

Part of an 18th century map showing the Île de la Cité and Notre Dame. Wikimedia commons.

Two things about my reaction to this fire trouble me. First, the fact that I had such faith that the authorities would protect Notre Dame, and that no serious harm could come to it. And second, that although I’ve frequently felt concern and sympathy for people and communities whose sacred places are threatened, I have never really been able to empathize. I knew that within hours of this tragedy, holier-than-thou comparisons would start rolling in: “You care about a cathedral, but not children separated from their parents at the border,” etc. I detest this phenomenon in general, because it’s a form of moral grandstanding, it implies that we don’t have room in our hearts and minds to simultaneously care about more than one thing, and because it does nothing to help or prevent either tragedy. However, having just returned from another place of great sacredness and history that is threatened, I could not escape some comparison-making myself.

View of Pueblo Bonito and Chaco Canyon from North Mesa. NG Mueller.

I spent three days last week exploring Chaco Canyon, an ancient city and sacred landscape in New Mexico’s San Juan Basin. Looking out over the canyon from Tsin Kletsin, a great house high on a mesa with views for hundreds of miles in every direction, I had a feeling very similar to the moment I stepped through Notre Dame’s doors for the first time and saw the high vault above me. I was struck by the hushed, respectful demeanor of all of the visitors I encountered while hiking and camping in Chaco, to the extent that in describing the mood to friends several days later I said, “It was like living inside of a massive cathedral.” Just as at Notre Dame, any visitor can feel the weight of human care that has been poured into that landscape. The great kivas and houses, the stairways cut into cliffsides, the roads striking out to distant mountains and mesas, the symbols carved into the glowing sandstone – all are parts of single place that is sacred to the Indigenous people of the Southwest. But although these buildings and features are protected within the canyon, the landscape in which they are imbedded is under threat.

Panorama from Pueblo Alto with the expanse of the Chacoan sacred landscape in the background. NG Mueller.

Yesterday as Notre Dame was burning, Brian Vallo, the governor of the Pueblo of Acoma, submitted written testimony to the House Committee on Natural Resources arguing for greater protection of the Chaco region, and more oversight by descendent communities over oil and gas development on surrounding federal lands. He writes “Chaco Canyon, and its vast landscape, are not abandoned …[it] is a living landscape, depended on by living indigenous communities…For Acoma, all ancestral pueblo archaeological resources are cultural resources, but not all cultural resources are archaeological in nature, and therein lies the major issue.” While federal law mandates consultation with archaeologists prior to development to prevent the destruction of archaeological sites and features, it does not mandate consultation with the communities who hold this landscape sacred, and who have other ways of defining places of historical and spiritual value. Some of these “cultural resources” may be other living things or entire ecosystems that are threatened by the rampant extractive industries around Chaco. The most recent volume of the Journal of Ethnobiology deals with similar issues of biocultural knowledge and activism. From British Columbia, to Patagonia, to Death Valley, these papers report on tactics for using ethnobiology to support the struggles of local and Indigenous people to protect their lands and sacred places.

Fajada Butte, home to a sacred astronomical observatory. NG Mueller.

Today, I am wondering how I can make myself feel the urgency of protecting Chaco as if I was watching a video of it going up in flames. We can’t rely on the authorities ensure the safety of what is irreplaceable and quintessential to the human spirit. In order to survive this era of unprecedented change and destruction, we need to develop a new sensibility as humans to register ecological, cultural, and public health disasters unfolding over the course of years as urgent crises – as on-going five alarm fires on a global scale. I hope that I can use the gut-wrenching sense of panic and loss that I felt last night watching my most sacred place burn to access this sense of urgency and apply it to my own works.

Comments (1)