Another Good Year for Learning the Gifts of Weeds

Another Good Year for Learning the Gifts of Weeds

By Tusha Yakovleva

I grew up gathering wild greens, mushrooms, and berries with my family. In Russia, where I am from, foraging for food and medicine is common practice. When I began farming in the Hudson River watershed* in 2012, I noticed edible weeds familiar from childhood growing between the crops I was tending. That discovery rekindled my interest in foraging and - with the help of excellent teachers, books, and time - I began learning the edible landscape of the region. My path has only gotten weedier since. I met many others who also wanted to connect with their surrounding plants. I began sharing my wild harvests and teaching aspiring foragers. And through those activities, I found that wild edible plants were an excellent point of entry for conversations about environmental responsibility, community health, and biocultural belonging.

I witnessed a rising hunger for wild plants in the region where I lived, for eating oneself into a sense of place. This desire grew so fast that essential aspects of relating to the land in reciprocal, responsible ways were not adopted by some newcomers to foraging. Some edible plants that grow slowly, live only in specialized habitats, and cannot tolerate extensive disturbance were being overharvested for commercial purposes, without consideration for the livelihood of those species or the whole ecosystem. Meanwhile, weedy wild edibles grew prolifically in already disturbed habitats and were largely ignored by commercial harvesters.

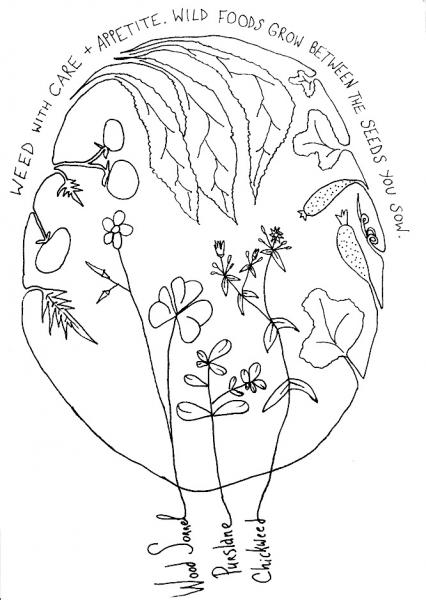

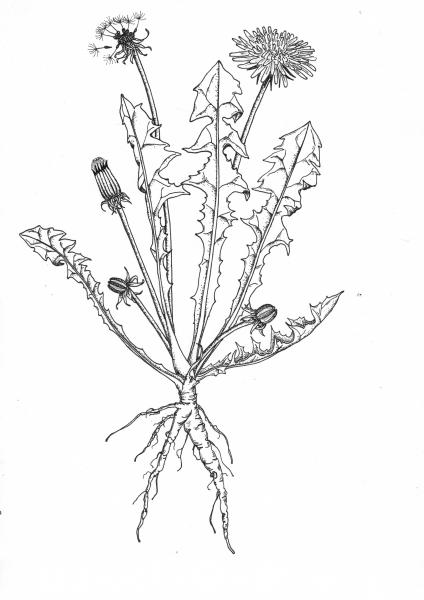

Weed with care and appetite. Illustration: Tusha Yakovleva.

As a farmer and forager, I saw the potential for symbiosis between these trends. My favorite foraging grounds were the fields and field-edges where I grew crops, largely because this was where I could harvest an abundance and diversity of foods and medicines without concern for ecosystem harm. It seemed that other vegetable farmers were also well-positioned to harvest weedy edible plants: they already stewarded habitats - tilled soils - favored by weeds and already had venues set up for distributing produce. Through conversations with other farmers, it became clear that considering edible weeds as supplemental crops was of interest to other growers. However, little information was available about how to manage, harvest, and share the stories of these unique crops with customers.

In an attempt to redirect a hunger for wild foods away from overharvested species and toward the weedy abundance of plants that love to thrive under human feet, I wrote a practical resource guide to support and empower farmers and gardeners wishing to add culinary weeds to their harvest lists. The guide - Edible Weeds on Farms: A Northeast Farmer’s Guide to Self-Growing Vegetables - came out this spring, shortly before the pandemic took hold on this continent. It’s a small weight offered to rebalance the narrative that weeds are bad. That side of the story has already received ample attention.

Image 1. Caption: Edible Weeds on Farms: Northeast Farmer’s Guide to Self-growing Vegetables - accessible for free online.

So-called weeds is a non-botanical term for plants that are encouraged to thrive and proliferate through our most common interactions with land, then vilified for getting in our way. I wish we didn’t treat plants as transactional goods. I wish we didn’t live in a world where nonhuman beings are treated as currency for fulfilling human wants rather than as creatures with whom we share a home. But, this is not the current state of our world. As such is our starting point, I want to aid in generating respectful, responsible, reciprocal relationships with the plants that are choosing to grow within this extractive system.

Weeds love disturbance and (most) humans love to disturb. Thus, humans and weeds share a long, intertwined history. For anyone who has ever turned the soil, weeds are our ancestry and our inheritance. One of my dearest mentors, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, sees plants as relatives. In her book, Braiding Sweetgrass, she shares a beautiful vision for how kind the world could be if only we remembered our relations. For anyone who relies on agrarian food systems, weeds - of all plants - may be easiest to see as family. We travel the world together; we grow our families together; we are in a long-term commitment to help each other survive.

Many disparaging words have been written against this branch of our family. Weeds have been blamed for working against the goals of food production, for stealing resources from more-deserving plants, for growing too far, too fast, and without discernment. Yet, their wild bodies are filled with food and medicine. They show up as first responders when land is turned up-side down and stitch the soil back together again. They feed pollinators and protect waters when other plants cannot.

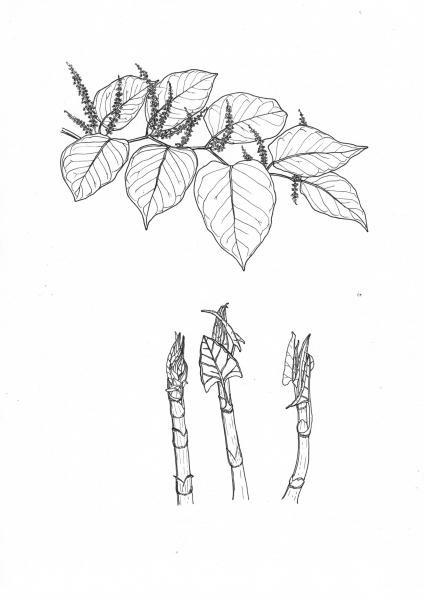

Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) - self-growing spring shoot vegetable rich in resveratrol, vigorous perennial commonly categorized as "invasive". Illustration: Eileen Wallding

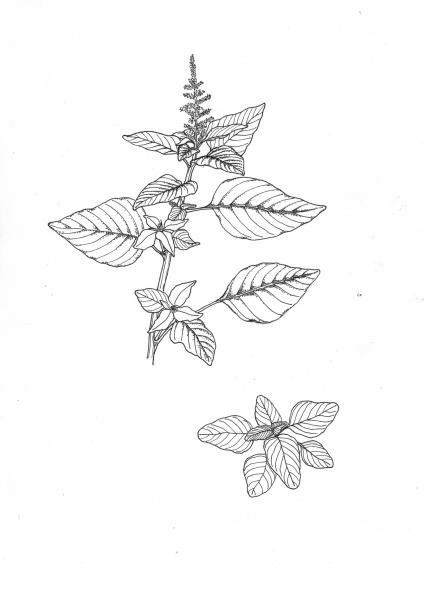

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp) - heat-tolerant summer green, protein-rich autumn grain; a superfood or superweed, depending on who you ask. Illustration: Eileen Wallding

As an ethnobotanist who introduces general audiences to edible and medicinal plants, I have seen a wave of interest in foraging and gardening swell in step with the pandemic this spring. The fault lines of the industrial agriculture system are showing brighter this year. Many people have suddenly found themselves putting more trust in seeds and soil to nourish their families over diffuse institutions dedicated only to growing wealth. It’s a good year to begin learning the gifts of weeds. Weeds carry stories of cultural survival. They have shown up in the most challenging times to feed generations of starving people across the planet. They are culinary archivists connecting seemingly disparate communities through shared stories of overcoming hunger by calling on the nourishment of omnipresent plants.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) - self-growing year-round vegetable commonly found in disturbed soils across the planet. Illustration: Eileen Wallding

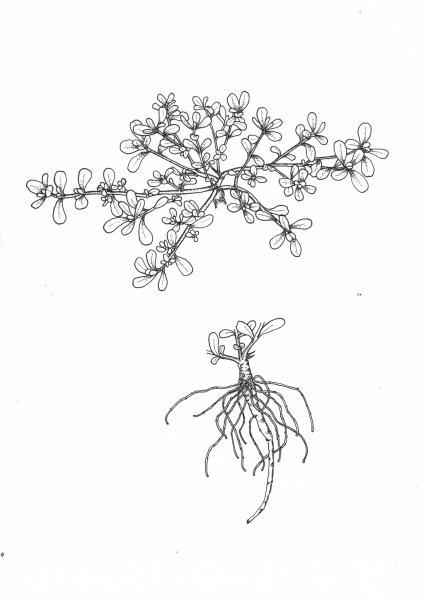

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) - self-growing summer vegetable commonly thriving in freshly turned garden soils, a rich source of Omega 3 fatty acids. Illustration: Eileen Wallding

--- *Ancestral homelands of Haudenosaunee and Mohican peoples, also known as New York State

Comments (1)